Qween Jean and Joela Rivera Are Making Space for Black Trans Lives

During a summer of civil unrest, when millions of Americans joined together in action after the police murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, Joela Rivera began to organize her first protest. She had already been taking to the streets with her fellow New Yorkers to demand justice for the hundreds of Black lives stolen by state-sanctioned violence over too many years. But while marching and chanting the names of victims like George and Breonna, she noticed that those of others like Tony McDade, a Black transgender man murdered by the police just two days after Floyd, were missing.

The erasure of state and police violence impacting Black trans lives at a majority of the protests that sprung up in New York City inspired Rivera to organize an action of her own—fittingly, in front of the historic Stonewall Inn on June 18, 2020. “I wanted to create a space where other organizers and other protesters can unlearn the transphobia and homophobia that they have within themselves that they think they didn’t have,“ the twenty-year-old Rivera says, “and also create a safe space for Black trans and Black queer people in the streets, where they can be one-hundred-percent themselves, fighting in a movement that is supposed to be for them.“

The choice of Stonewall, where queer and trans people revolted against police raids, harassment, and violence in 1969, was more than just symbolic. It was a reclamation of the historic gay bar (which is presently draped with corporate advertisements and frequented by tourists) where those conflicts led to the beginning of the modern-day LGBTQ+ rights movement. It was also a reminder of the ongoing systemic violence against LGBTQ+ people, which particularly impacts Black and Brown queer and trans individuals.

Qween Jean, twenty-one, also didn’t see Black trans experiences being uplifted in the rallies and protests. When she arrived at Stonewall the evening of Rivera’s protest, she saw a sign that included the names of Tony McDade and Layleen Polanco, an Afro-Latinx trans woman who died in solitary confinement at Rikers Island two years ago, and she felt welcomed. Since that initial rally, where they first met, Rivera and Jean have taken a one-off protest and turned it into a weekly event, cultivating a unique community of people who come out every Thursday to demand Black trans liberation.

“This is truly our life, and we’re going to take a moment to hold space,“ Jean says of the Stonewall Protests, which have doubled as a healing space for queer and trans people. “I think on the surface, people may feel like, ’Oh, this is just the time to be able to get together,’ but this is the time for us to heal as a community,“ she adds. “The Black Lives Matter movement traditionally does not always include Black trans, Black queer, nonbinary siblings, but it does now. That is a testament, I think, to the work of our community, the advocacy of showing up, being visible, being loud, being proud.“

While Floyd’s death served as a catalyst for many— Rivera and Jean included—to take to the streets and demand justice, it was not this single event that kept them organizing. As Black trans women, Rivera and Jean are acutely aware of the epidemic of violence impacting Black trans people, disproportionately taking the lives of Black trans femmes. In 2020, while the nation reeled over the loss of over 345,000 Americans to the Covid-19 pandemic and Black people grieved over continued murders at the hands of police, the deaths of Black trans folks compounded the grief in their community.

At least forty-four trans people, the majority of them Black and Brown trans women, were murdered last year. Advocates who track violence against the LGBTQ+ community note that the highest recorded number of trans homicides before 2020 was twenty-seven. Routinely, these deaths go unnoticed both within and outside of the broader LGBTQ+ community, and often the police do not pay attention either.

“Abolition now!“ is the rallying cry every week at the Stonewall Protests, usually as police circle the area, often violently arresting the protesters, including Rivera and Jean. The message is clear: Safety is found in community, not policing. We can take care of each other’s needs and support one another. One way the Stonewall Protests provide for the community is by offering tangible support in the form of mutual aid, routinely giving free meals to protesters and New Yorkers experiencing homelessness. “Another thing now that we’re really trying to focus on that was more of a dream of mine is being able to acquire housing and property in the city,“ Rivera says, “so that we can not only reach out to Black trans youth who are around the country and say, ’There’s a place that you can come live in if you can’t stay in your home,’ but also get sustainable housing for so many Black trans people from across the country in the city, as well as Black queer people.“

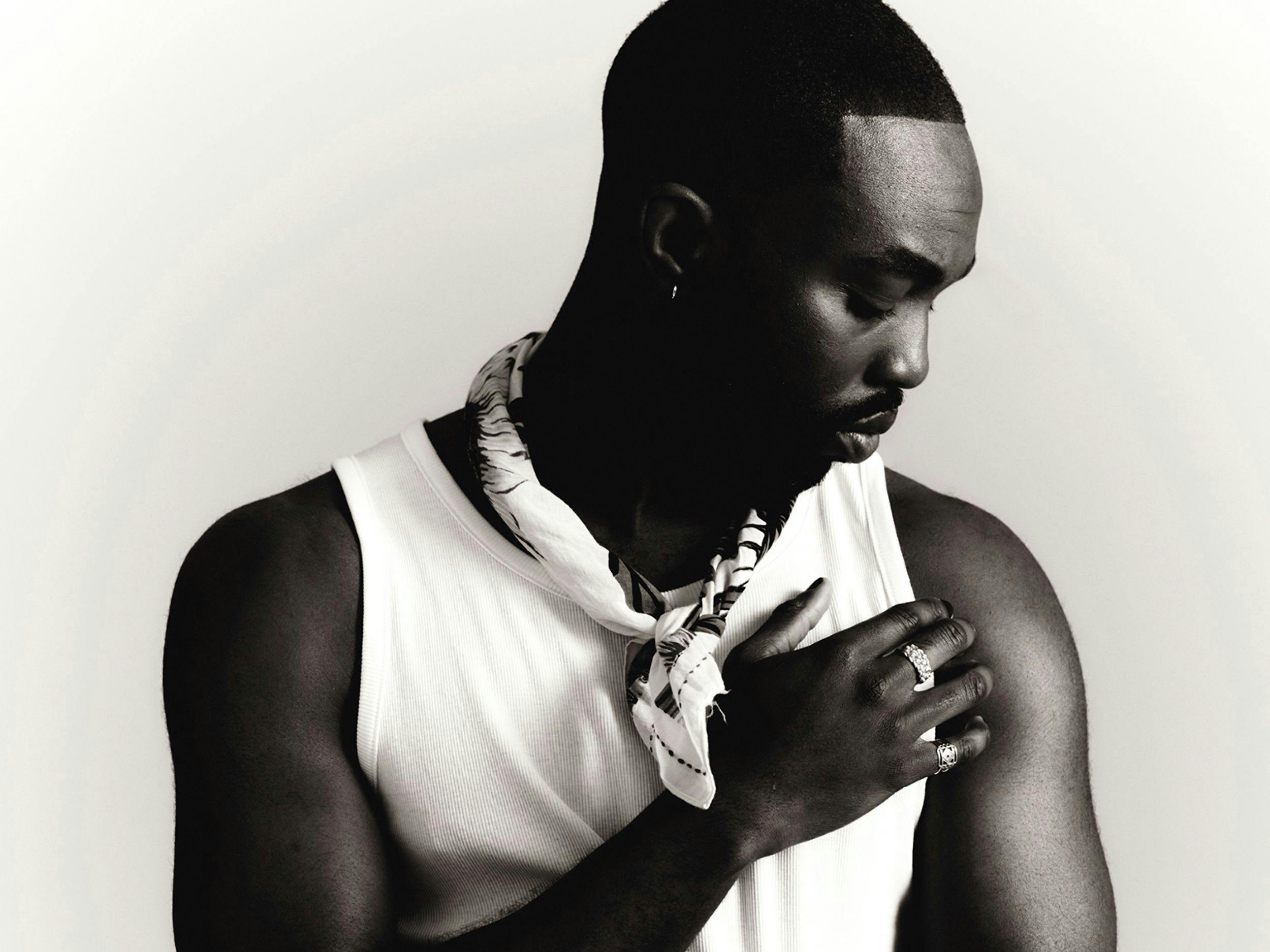

While the protests spotlight the violence impacting queer and trans communities, they are not somber. Jean and Rivera are intentional in bringing joy each week, taking a page from the queer ballroom scene with music and dancing and encouraging protesters to turn a look and dress their very best. Each week a swath of photographers attends, documenting the joy and resistance of the Stonewall Protests, a divergence from the guidance given by organizers last summer that encouraged people not to take photos that would make protesters easily identifiable. Video and photography have become an integral part of the weekly Stonewall Protests, with photographers like Ryan McGinley capturing beautiful action shots and portraits of attendees.

“This is not about show. This is not about pomp, this is not about circumstance,“ Jean says about showing up in sequined dresses and lavish attire. While the Stonewall Protests regularly block traffic and disrupt unsuspecting New Yorkers’ outdoor dinners, Jean and Rivera are not concerned with being identified by the police. For them, showing up and making space for Black trans joy is just as important a disruption as the stopping of traffic. “So we show up,“ Jean adds. “We show up in our full regality because we are indeed regal. We are indeed divine. We show up because intrinsically this is who we are, historically this is who we’ve been.“

As the majority of New Yorkers and Americans across the country have moved on from last summer’s historic uprisings, Jean and Rivera have continued a steady drumbeat. Past the summer into the fall and through the winter, the Stonewall Protests have continued each week, consistently bringing out at least sixty to eighty people. “When I came into the movement, I already knew what it was going to give a month from now, two months from now, six months from now. I knew people were going to stop coming,“ Rivera says. “I knew for a lot of people, this was just an excuse to be able to get out of the house from being inside all this time. I knew it was all performative. That’s why one day wasn’t enough. One Thursday could not happen enough. Here we are over thirty-five weeks in, and it’s still not enough.“ [Editor’s note: Since this interview was conducted, the Stonewall Protests have celebrated their first anniversary.]

Despite the cold weather, the continued threat of arrest by police, and the waning attention to the ongoing violence impacting Black and trans communities, Rivera and Jean continue to show up to demand Black Trans Liberation. They’re honoring Stonewall veterans like Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, continuing a legacy of protest. “I think that end goal, it has to be Black liberation. That’s when people will stop, thousands of years from now,“ Rivera says. “That’s when people will stop. That’s when Black trans people and Black queer people will stop, when Black liberation is achieved for all Black people. Because we can get two apartment buildings tomorrow, but Black people are still being murdered by the police. There’s so many goals before we reach the ultimate one, Black liberation. That’s my end goal.“

Read this story and many more in print by ordering our inaugural issue here, with all net proceeds from Jean and Rivera’s cover going to Black Trans Liberation.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.