How the Community Feeds Itself

Love comes in many forms. And while it might seem easy to categorize the slew of refrigerators that have been appearing on sidewalks across New York and other American cities as just grassroots solutions for food insecurity, these seemingly simple appliances represent so much more. “Food is more than physical sustenance, food is a nourishment of the soul,“ says Tatiana Smith, the founder of a Jersey City community fridge. “It’s filling a physical need and a psychological need for love. It’s saying, ’People care enough to nourish you.’“

There are no official guidelines for what constitutes a community fridge, but there are commonalities. Most are free sources of fresh food and produce accessible to anyone who lives nearby without restriction. They are usually managed by a small group of locals who work with businesses and organizations to stock each fridge with unused or leftover goods. “On a micro-scale, each fridge fits into each community. It suits the needs of the community,“ Smith says. “People who manage the fridges are paying super close attention to what the community needs, and that can vary neighborhood to neighborhood and even block to block.“

The recent growth in the fridges can be attributed to several factors: the crippling effects of Covid-19 on the economy, an increasing awareness of food waste, and the power of social media to drive visibility. At its highest point in April 2020, the unemployment rate in America hit nearly fifteen percent. At the same time, restaurants and other food-based businesses struggled to manage supply and demand amid constantly shifting government policies, while the public has become more attuned to the consequences of throwing out perfectly fine and edible food. An estimated eighty billion pounds of food, nearly forty percent of America’s supply, is wasted each year: a major contributor to the climate crisis.

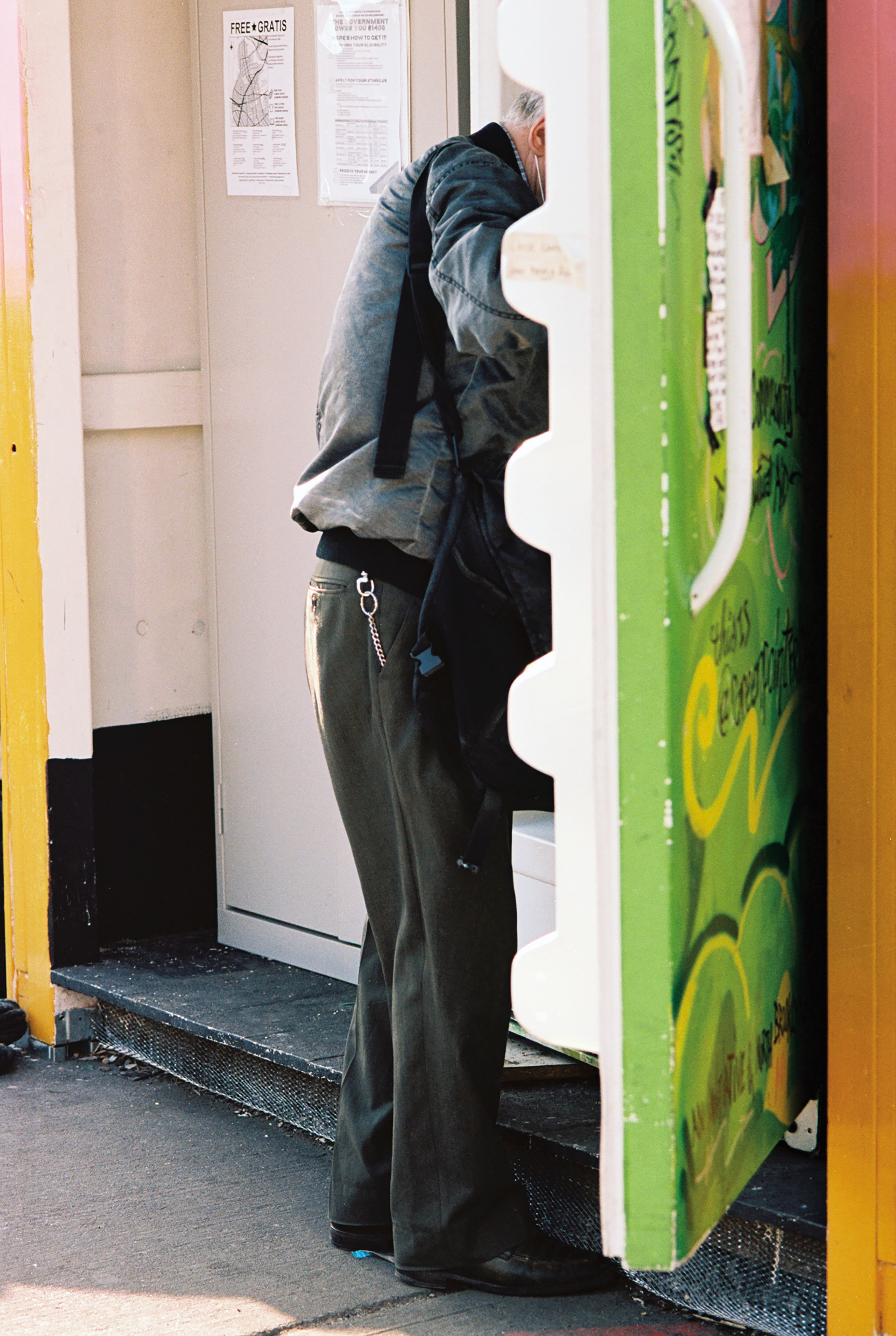

As highly visible representations of their neighborhoods, each fridge has also become an outlet for its community’s creative expression, a visual bulletin board for graphics, graffiti, and text with a hyperlocal focus. Their vibrant designs have also created momentum on social media, helping to not only amplify updates on available food but also showcase local spirit.

That prominence is inspiring others to get involved as well, like Alexandra Shoneyin, who opened a community fridge in Staten Island after seeing similar ones on social media. “I was always interested in building community,“ she says. “I reached out to In Our Hearts,“ a New York City network of progressive collectives, projects, and individuals, “and they helped create a fridge. They suggested that we start an Instagram and it created a ripple effect, resonating with other people in the community that wanted to make a difference.“

“It’s a community effort,“ Smith agrees. “We work with different nonprofits, pantries, and restaurants that will donate or set aside food for a day. I’ve got it down to a system where there is food every day.“

Where larger organizations failed, nimbler, more focused solutions stepped in. Community fridges connect vulnerable residents with nearby food from restaurants, grocery stores, and other organizations that would otherwise go to waste. “Local businesses in the area provide food to the fridge,“ Shoneyin says. “We try to keep it to healthy food, but really people give whatever they can. We’ve also been able to partner with food pantries and local churches. We have maybe ten or fifteen local partnerships, but really it’s people from the community who fill the fridge.“

The fridges also provide an alternative to conventional solutions like food pantries, which can have literal or psychological barriers to entry: “The biggest thing is the stigma,“ Smith says. Fridges eliminate the need for means testing by reframing the conversation around mutual aid as opposed to welfare. “With charity, there is a power dynamic,“ she adds.

Still, the fridges are not entirely immune to this concern. “There’s also a stigma around who is food insecure and an assumption that people who are food insecure are homeless, which is not true,“ Shoneyin says. “We’re noticing we need to do some education as well.“

The ultimate goal isn’t just to address food insecurity but to rethink the way that neighborhoods can provide—and show love—for their own. “If communities can take care of each other, we can alleviate the other maladies within communities,“ Smith says. “Education, safety—so many social ills come from not having your basic needs met.“ The idea of a community fridge—a completely free, publicly available resource—can seem radical to Western perspectives, but the reality is that principles of mutual aid and collective living have long helped communities flourish both inside and outside the United States. “I did some internships in South Africa and Rwanda,“ Shoneyin explains, “and living there, I experienced how communal cultures are ingrained in those societies. I was hoping to bring that to Western culture. I feel we’re shifting mindsets and allowing people to unlearn some of the misconceptions they had. I think that’s what we’re doing, we’re just doing that through food.“

In the long term, the idea isn’t for the fridges to eventually disappear. On the contrary, the whole point is that the fridges and what they represent—mutual aid, healing, nourishment, compassion—should become ingrained into our way of life. Smith is expanding her provider network, and Shoneyin is connecting with local schools and farms to run a joint program that teaches residents how to grow their own food and contribute to the community. “We’re using food to create larger conversations,“ Shoneyin says. These fridges are widening the lens and beginning a conversation that starts with a community, but ultimately includes us all.

Read this story and many more in print by ordering our inaugural issue here.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.