Dress and sleeve by Rui. Vintage skirt from Albright Fashion Library. Earrings by Dinosaur Designs. Bracelet by Alexis Bittar.

Raquel Willis Wants Gender Liberation for All

Raquel Willis’s rise to prominence as one of the best-known Black trans activists in the country wasn’t planned. Her life was shaped through the process of coming into herself against the backdrop of a constant onslaught of violence against Black and trans communities just before the boom of trans visibility less than a decade ago. Willis started her career as a journalist in local media in Monroe, Georgia, in 2013 and within a year began to use her growing digital platform to speak out on the homicides of trans women and Black people killed by the police. In Willis’s new debut memoir, The Risk It Takes To Bloom: On Life and Liberation, she writes a personal and political story of fully realizing her womanhood and becoming the advocate she is today.

Over the past several years, Willis has held key positions as a national organizer at the Transgender Law Center, Out Magazine’s executive editor, and director of communications at the Ms. Foundation for Women. She’s the co-founder of the Trans Week of Action and served as executive producer and host of Logo’s Trans Youth Town Hall series. In her book, she writes about her gender journey and life growing up in southern Georgia, her work as a media strategist and community organizer, and calls for us all to join in the collective work of liberation.

Willis and I first met in the dressing room of a lesbian bar in Atlanta called My Sister’s Room just a few months after she started her journalism career. We were in a drag competition—it was one of the few dozen times I have ever done drag—and Willis stood out above the rest of us as her drag persona, Rebel Devoe. She performed Lady Gaga’s “Applause“ with a rip-away bra, revealing a silver sequinned moment that brought the house down. I believe she won—or at least in my eyes, she did.

Dress by Tia Adeola. Sleeves and necklace, stylist’s own.

When we meet for dinner to discuss her new book, Willis and I talk about her relationship with drag, which she writes provided a playground that helped her explore her gender: “Drag was an important gateway for me because it gave me a step to accepting what I would eventually understand to be my inherent transness that I had carried since I was a kid,“ she tells me. This is true for many trans people but despite the rich history of trans people in drag, the art form can still be somewhat contentious within trans communities, particularly during times when right-wing political actors work to conflate the art, gender expression, and trans identities as a means to restrict or prohibit any deviation from gender norms.

More recently, as anti-trans legislation sweeps the country, some tensions have arisen between some trans people who present as more clearly conforming to the gender binary and those whose gender presentation is more disruptive. “I’ve never felt threatened by people who have maybe a queerer gender expression or non-binary folks or genderqueer folks,“ Willis says. “I also think that a lot of us came from that space so it actually is a disservice for more binary trans people to be threatened by those who blur the lines. I actually think there’s a power in that. I don’t want to make the assumption that every non-binary person cares about gender less than every binary trans person.“

It’s with this nuance and expansive view that Willis writes about gender—although her memoir shouldn’t be seen simply as a trans memoir because that’s “reductive as fuck,“ she quips—and about our collective liberation from cis-hetero patriarchy.

Vintage top by Jean Paul Gaultier from Albright Fashion Library. Vintage shorts by Magda Butrym from Albright Fashion Library. Veil and tights, stylist’s own. Shoes by Roger Vivier. Necklace by Alexis Bittar.

Born and raised in Augusta, Georgia, Willis is the youngest of three from a traditional southern, Black, Catholic home. In her tight-knit family, the response to her sexuality as a young person varied, with the men in her life having some of the worst reactions. She writes in her book about the expectations she faced at home, particularly from her father, of the man she was supposed to grow into and how his untimely death when she was nineteen relieved her of those imposed conditions. “Your death saddened me, but it also freed me. I could love you and not fit your mold. I could love you and I didn’t have to see myself as a failure for not being the epitome of Black masculinity,“ she vulnerably writes in the chapter “Letter to My Father,“ the first of four to individuals whose deaths had an impact on the trajectory of her life sprinkled throughout her memoir. Tragically, her father never got to know the woman that she is today, but the rest of her family got to—including her mother, sister, and brother—and they grew in their relationships to reach the loving and affirming place they’re at now.

While her father’s death gave Willis the space to transition, it was the death by suicide of Leelah Alcorn, a trans seventeen-year-old, in December 2014 that pushed her to speak out more for trans people, especially the youth. Willis was still at her first job after college and not out to her employers when she posted a tearful reaction video to Alcorn’s suicide letter, which was posthumously published on Tumblr and in which she pleaded, “My death needs to mean something…Fix society. Please.“ Willis’s video picked up views and got the attention of a BBC producer, who invited her to speak on a show about the violence trans people are facing. “You taught me I am obligated to others, my community, and younger trans folks to blaze a path,“ Willis writes to Alcorn. “I can’t bring you back or the souls of our siblings who similarly departed this world, but I’m vowing to do my part in an attempt to fix society. I will demand the liberation we deserve.“

“Leelah Alcorn publishing that suicide letter on Tumblr shifted so much for me in terms of, even though I didn’t see what my career could become or what I could do, that doesn’t mean that I get to just wallow in the shadows,“ Willis says. Alcorn’s death, coupled with the growing Movement for Black Lives in response to police killings of Black people, activated Willis politically and started her on a unique path straddling media and advocacy.

Over the next several years, Willis worked in and out of media institutions and nonprofit organizations, always focusing on elevating the stories of trans and Black communities. An internship at Solutions Not Punishment Collaborative, an organization dedicated to criminal justice reform and prison abolition in the Atlanta area, was Willis’s first political home. It was there, she writes, that she began wrestling with and nurturing her politics which have shaped her work since.

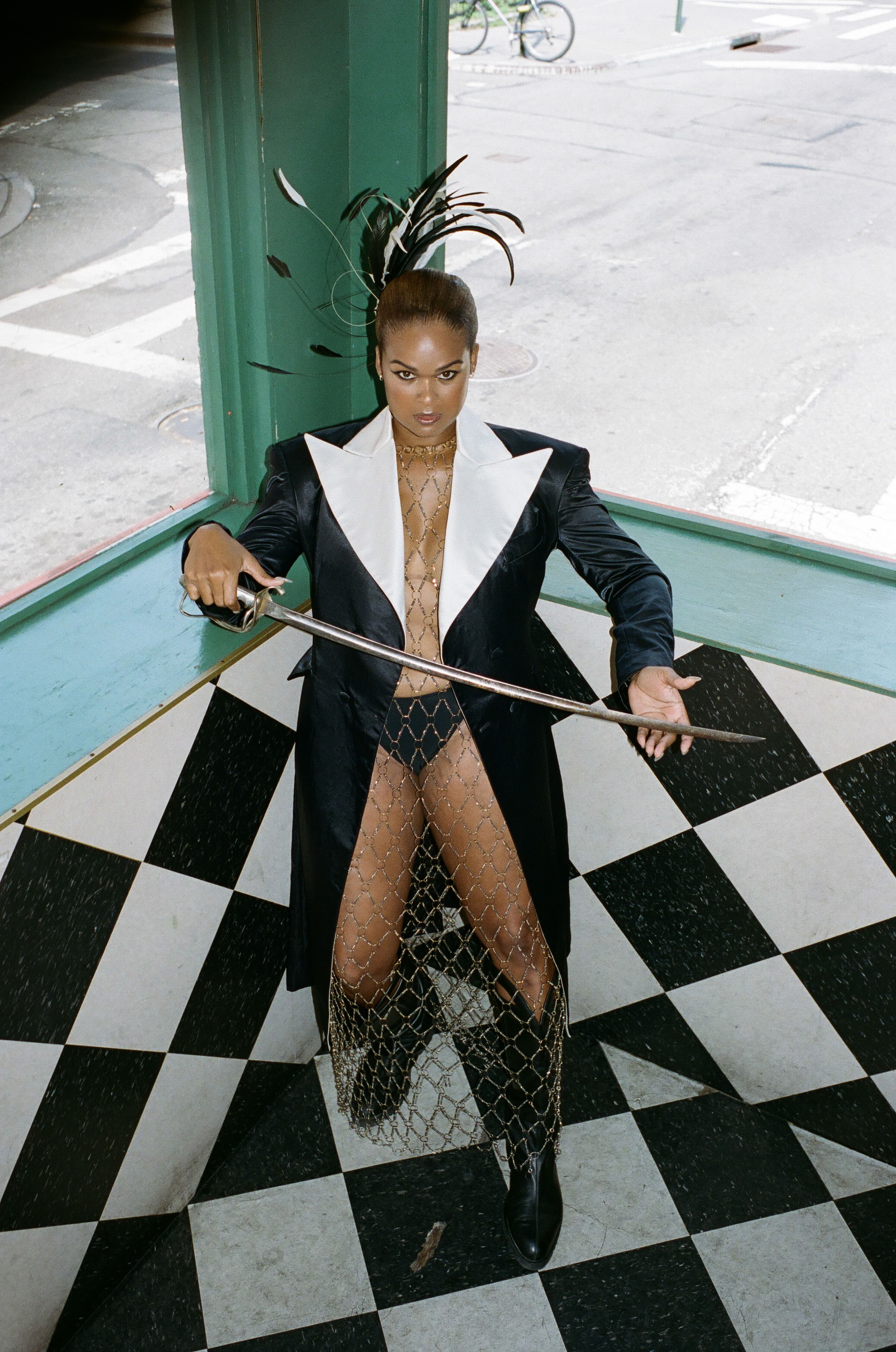

Jacket by Willy Chavarria. Vintage dress by Paco Rabanne from Albright Fashion Library. Vintage headpiece from Albright Fashion Library. Boots by Telfar. Earrings and sword, stylist’s own.

Shortly afterward, Willis joined the communications department at the Transgender Law Center (TLC), an advocacy organization that works to secure civil rights for trans and gender nonconforming people through impact litigation and education, a position that brought her to Oakland, California, from Georgia. Her time at TLC was mixed, disillusioning her about what it was like to work full-time at a social justice-focused nonprofit organization. There were internal tensions between upper management and lower-level staff about organizational priorities and what Willis recalls as a lack of urgency to end the epidemic of violence against Black trans folks.

In “Letter to Chyna Gibson,“ a 31-year-old Black trans woman who was killed in 2017 in New Orleans, Willis discusses her frustrations with TLC at the time. “Advocacy. Capacity building. Impact litigation. So much jargon is thrown around as if it means anything to those of us being shot, shanked, and murdered. What good is an organizational strategy if none of the people you aid are Black and trans?“ she writes. “I was naive to think that working at a nonprofit would automatically translate to championing Black trans lives.“

During our interview, I asked Willis about her critiques of TLC and she responded that the situation was much more pervasive than just her experience and that they should be applied more broadly to anti-Blackness at LGBTQ+ nonprofits writ large. “I don’t want other nonprofits to think that they’re off the hook. I’m telling you that this was my experience at TLC, but the Human Rights Campaigns of the world are not off the hook, the LGBTQ Task Forces are not off the hook and so on and so forth,“ she says, adding that TLC is still one of the best places to work.

Indeed, many of the national gay rights organizations have claimed to champion the rights of the entire LGBTQ+ community but historically failed to center trans communities, and most have only recently begun to try and incorporate a racial justice lens into their work. The LGBTQ+ movement is rife with current and ex-employees at nonprofits who are disillusioned by unmanageable workloads, low pay, and lack of decision-making power. This has led to a recent push for unions at many of the organizations, including Lambda Legal, the Trevor Project, Housing Works, the NYC Anti-Violence Project (AVP), and others.

Still, despite the internal strife, Willis is proud of her work and accomplishments during her time at TLC. Within a year, she moved from the communications department and assumed the role of national organizer, in which she began the Black Trans Circles program, which focuses on developing leadership and cultivating healing spaces for Black trans organizers in the South and Midwest.

Dress by Collina Strada. Vintage belt from Cherry Vintage. Shoes by René Caovilla. All jewelry, stylist’s own.

While she worked at TLC, Willis continued to write and build a digital presence as a thought leader on gender, race, and social justice. Her prominence led to a speaking opportunity in 2017 at the famed Women’s March. While it was meant to signal the inclusion of trans folks, Willis’s microphone was cut off before the end of her allotted three minutes because the program was running behind, a move, she said during her book launch event, that she felt prioritized celebrity over activism. Her experiences of being sidelined have given her heavy skepticism about nonprofits and certain organizing spaces. “I fought for my womanhood. I fought for my name, I fought for my pronouns. I fought for everything else. I’m fighting to define myself on my own terms right now, outside of these institutions,“ says Willis, as we talk about her work both within and outside such organizations. “I know what it feels like, and many of us know what it feels like, to feel small even in these institutions that we believe in.“

The following year, Willis’s writing and her growing platform brought another opportunity, this time in New York City, when she accepted a role as executive editor at Out Magazine, which created a newfound media frenzy as she became the first trans editor to hold that position. While her time at Out was tumultuous, burdened by a history of unresolved financial troubles and failure to pay freelancers, it was there that she was able to pitch and write a cover story on Layleen Polanco, an Afro-Latinx trans woman who died while being held in solitary confinement at New York’s Rikers Island in 2019, and her surviving family. This article was part of the Trans Obituaries Project, a GLAAD Media Award-winning series of profiles of trans and gender nonconforming people who were killed in 2019 as well as a thirteen-point solution to end this epidemic of violence derived from conversations with trans organizers on the frontlines across the country.

“This is just a sampling of the deaths,“ Willis says about the fourth and final letter in her memoir, to Polanco. “I could have written more letters, but these were some of the most pivotal lives that were lost. What I wanted to get at was that I think almost everyone, especially now, understands that the deaths of these people, whether they knew them or not, can serve as opportunities for us to bloom into something else or to be changed by them.“

Vintage jacket by LaQuan Smith from Albright Fashion Library. Vintage bra by Magda Butrym from Albright Fashion Library. Vintage skirt by Helmut Lang from Albright Fashion Library. Earrings, stylist’s own.

The death of Polanco changed me as well. After meeting Willis in that backroom of a gay bar, our paths crossed time and time again as we both found our footing as organizers and communications experts in the LGBTQ+ movement space. I previously worked as director of communications at AVP, where I first connected with the Polanco family just days after Layleen died. Willis was among the first people I texted to speak at the initial rally AVP organized to demand justice for Polanco and amplify her story.

Even now, Polanco’s harrowing story within the criminal legal system is the framing for one of two podcasts Raquel is executive producing with iHeartMedia. The first episodes of Afterlives are out now, discussing the murders and deaths of trans people of color and the impact they have on our community, with the first season focusing on Polanco. The second podcast, title pending, is set to debut in 2024 and will focus on queer and trans youth in red states, sharing audio diaries about their lives over the course of a couple of weeks, touching on everything from “navigating healthcare to friendship, crushes, passion, and so much more.“

Willis’s decade of organizing and media work culminated during the uprisings of the summer of 2020, when she and I, together with other queer and trans creatives and organizers, co-organized Brooklyn Liberation: An Action for Black Trans Lives, which brought together an estimated fifteen to twenty thousand people. In the final chapter of her book, Willis recounts the historic event as one of the four speakers—and this time, her mic was on.

“I believe in my power! I believe in your power! I believe in Black trans power!“ Willis’s voice thundered over a sea of protestors in white, an homage to the 1917 Negro Silent Protest Parade. In a call and repeat, Willis charged the crowd to believe in their power to create the change we need to build a society where trans people can live free from violence and have access to the basic human rights of “safety and housing and healthcare.“

All clothing by Issey Miyake. Hat by Xtinel. Shoes by René Caovilla. Earrings by Alexis Bittar.

Indeed, as Willis wrote for Cero Magazine earlier this year, “Now that we are more visible than ever, we are finding that we are more vulnerable than ever as well.“ One of the main broken promises of trans visibility has been the insinuation that trans people would receive what they need through media representation but more visibility hasn’t changed the material conditions of the majority of trans people. In fact, Willis’s memoir comes during a year in which over five hundred pieces of anti-trans legislation have been introduced across the United States and with historic homicide rates of trans and non-binary people—something not lost to her.

As a journalist and activist, Willis’s work follows the legacies of other Black women like Ida B. Wells and Monica Roberts, who used their writing to tell the truth about the violence impacting their communities. Her revolutionary storytelling work creates space for trans and non-binary people to share their experiences and is fueled by the memories of those who have been lost. As readers of Willis’s memoir will learn, she’s a force, committed to our liberation, and we’re only just beginning to see her petals bloom.

The Risk It Takes to Bloom: On Life and Liberation is out now. Be one of the first to see this story and many more in print by preordering our seventh issue here.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.

Dress by Miss Claire Sullivan. Shoes by Manolo Blahnik. Earrings, stylist’s own.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.