In the Room with Peter Do and Ocean Vuong

I know little about the fashion industry—and so was a bit nervous meeting Peter Do, one of the most exciting and innovative designers working today. Within a month after our meeting, Do would be tapped to lead Helmut Lang as its creative director, the first Asian-American to do so in the house’s storied history. Shortly after, Rihanna would be spotted sporting his oversized blazer, the same one he wore for our shoot accompanying this interview.

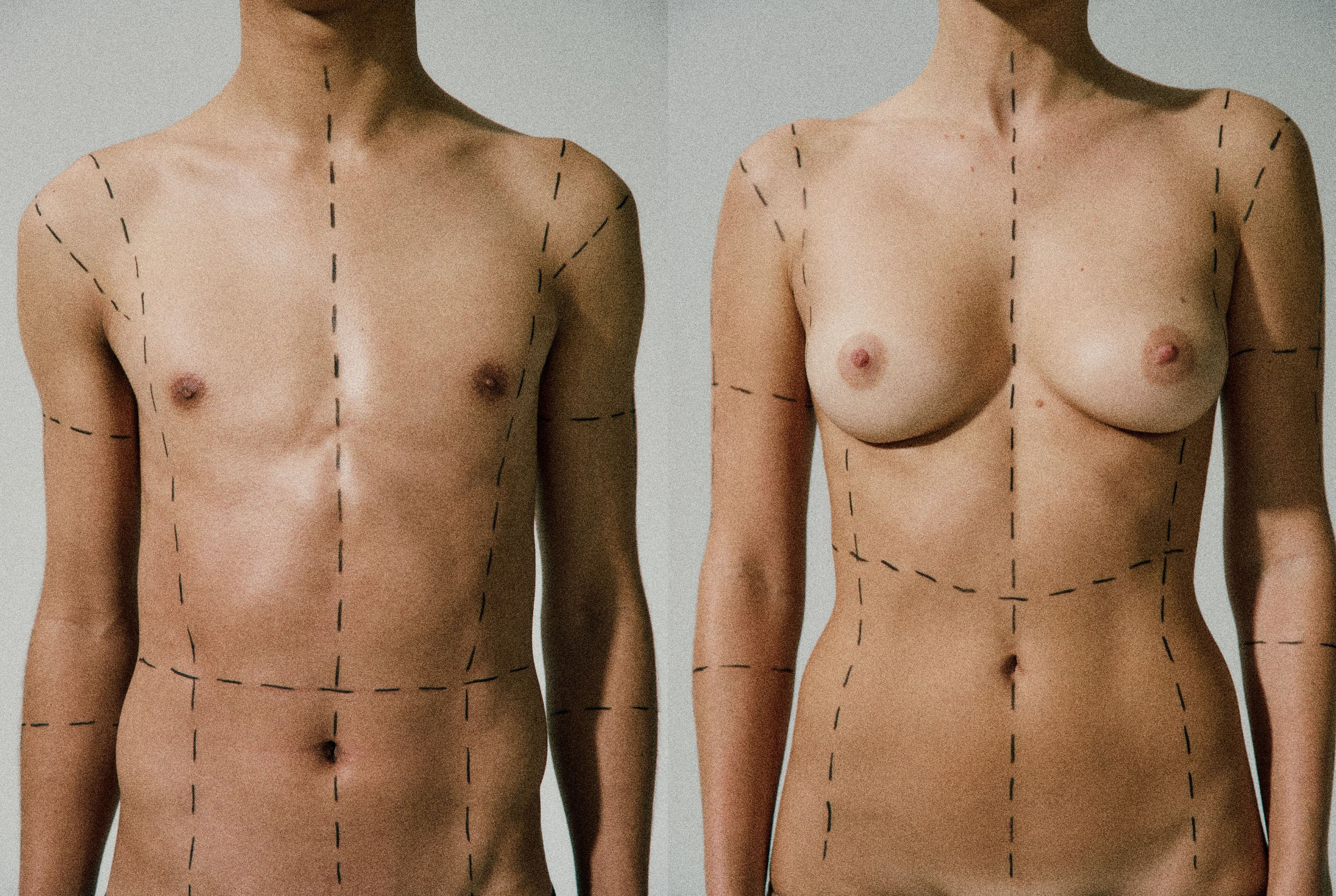

Beyond his reputation for sharp lines, sleek yet bold monochrome pieces with diaphanous meshes that blur and derange gender borders, he’s also known for keeping a low profile, which includes wearing a mask for all public-facing events. For the “fashion world,“ where brands are often built on personalities that lean heavily on their creators’ image, the preservation of one’s face might be read as itself a stamped “trademark“ of a mystical and aloof prodigy. But after making my way down the long, wide hall of his Sunset Park studio, flanked on both sides by racks of black and white garments the length of subway cars, I found Peter behind a room walled by warehouse windows overlooking the Upper Bay, the glass silhouetting the designer in the ink-black shade of his pieces, and realized there was something more substantial about his choice to turn away. As I entered the room, I was immediately met by a wave of laughter. It was Peter, unmasked and giggling among friends, a white grin flashing under the bill of a carbon Carhartt cap. Almost instinctually, we embraced.

What became clear to me, through Peter’s warm and jovial presence as we spoke, often punctuated with more table-slapping laughter, was that the guarding of his face was not a public-facing act at all, but one meant to safeguard his agency as an artist, to hold a space where his amicable and bright demeanor can be protected in a culture where a façade of austerity can be mistaken for genius. Behind the mask, Peter Do can be fully himself: bright, eager to talk, and quick to embrace his vulnerability—but more so, eager to center his ideas over himself. While we spoke, his face open and full, I was reminded of the Vietnamese saying around shame and public embarrassment, mất mặt (to lose your face), a saying I heard often growing up. “Don’t you lose your face,“ my mother would say as I stepped out of the house into the rest of America. Peter has taken this impulse one step further; he saves his face only for those he chooses, and thereby reaffirms the role of the artist as both maker and one who controls his own revelations.

OCEAN VUONG One of my favorite poets, Natalie Diaz, writes, “I do not want to make a museum of myself,“ and I think that awareness of cultural impact is really integral. I’m curious, in that sense, what drew you to making clothes? In our Vietnamese culture, it’s actually common to tailor, fabric repair being the lifeblood of our communities. You go to chợ. I’m from Gò Công, where we have one, every village has one. You go to that market and you see the bolts of thread, you see the fabric makers, their pride. You don’t see that as much in the American landscape, where the material of labor is often hidden. We’re so final-product–oriented here. When I go to my village in Vietnam, you see that so many hands have touched your clothes. What drew you to fabrics and fashion?

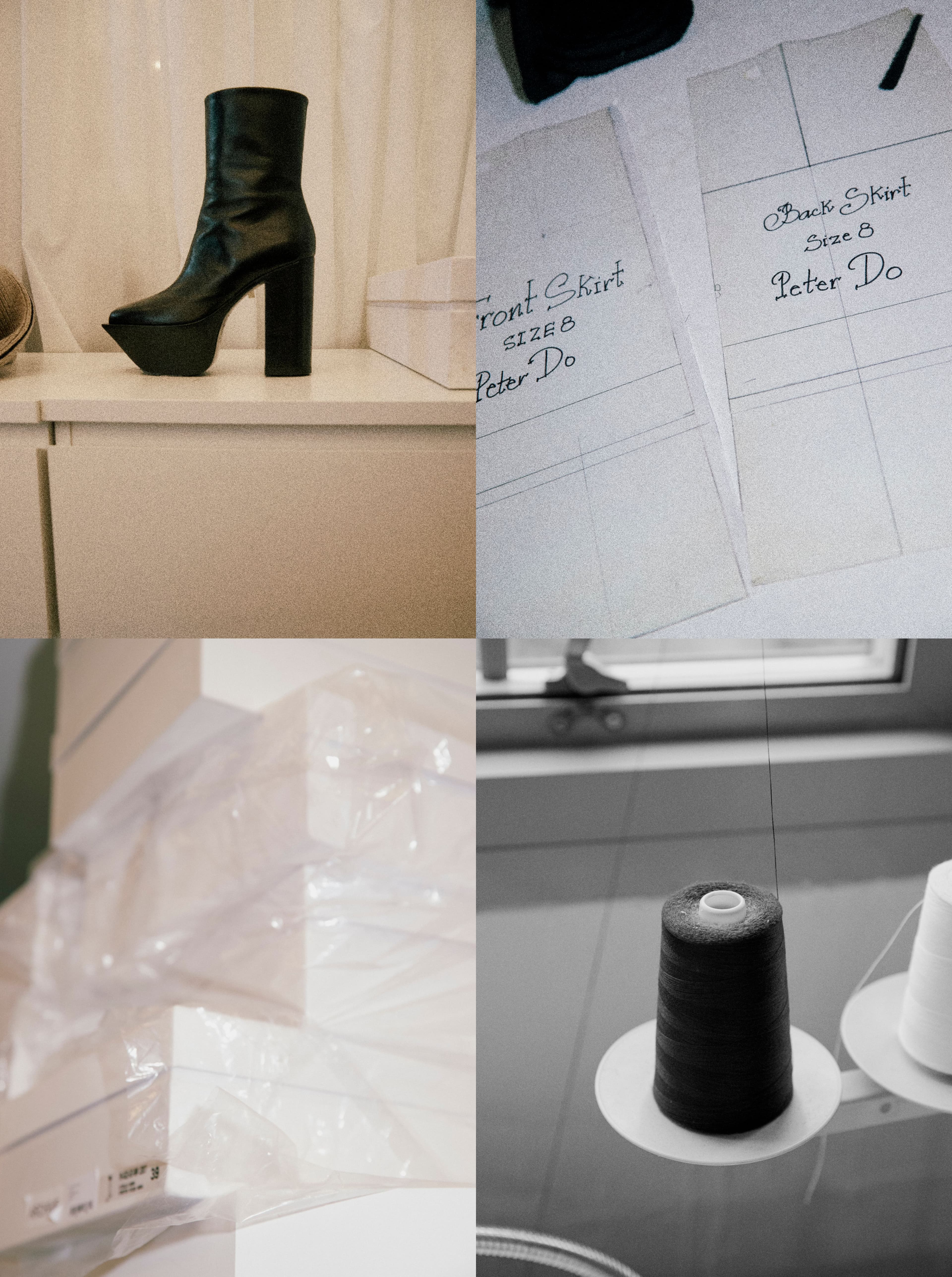

PETER DO My first initial experience with fashion was my grandma, we had an old Singer sewing machine. I was really curious about this old machine, you had to crank at it.

OV My dad had that too. They’re Chinese and they were all thợ may.

PD Yeah, but I feel that’s quite common knowledge, people make their own clothes. My grandma would patch things and sew, basic things like that. If you need something, either you go to a local tailor, the lady down the street, and make your school uniform. Or my grandma, if something’s broken, she was like, “Patch another thing on top and we’ll sew it together.“ If the button was broken, she taught me how to fix the button. That was my first introduction to clothesmaking—out of necessity.

OV Wow.

PD The concept of buying new clothes was not something that was introduced. I didn’t know that was an option. I didn’t know that I can go out there and buy clothes. It wasn’t accessible in that sense. I remember owning very little clothes, this one drawer and it’s just a few tank tops. You have one pair of flip flops or one thing you wear to school, which is the red scarf, short-sleeved shirt that has your name on it, embroidered, and then just black or navy pants. That’s basically what you have, and then maybe you’re lucky, you have a suit, a blazer, that was passed down from your cousin maybe, and then you just pass it around. When you grow out of it, it goes to the next kid.

PD It’s communal. The pieces, it’s not just like, “Oh yeah, let’s go get you a blazer.“ It’s like, “Okay, it’s your birthday. Today you wear this blazer.“ I have so many photos of me just holding my cake and my family saying, “Chúc mừng!“

OV But I think the beauty there is that it shows how precious clothing and fabric is, that it’s an extension of the family and it’s not singularly one’s own. Possession is evacuated from this idea because its origins are multitudinous. Similar to how we cook, you see that everything is slow-made. You mentioned that you work very slowly. I’m curious where that diligence comes from to slow down. Because I see so much of that in Viet culture. In fact, I don’t even think there’s even an idea of slowness and quickness, but time is just very different in the Vietnamese context. Even our language, we don’t really use the past tense. We have to use rồi to have the past tense. Otherwise everything is floating up so that time is wobbly and warped. What was your thinking around slowing down? You talk about the integrity of the threading and the making of the work, particularly in a day in America where everything is so fast-paced and result-oriented.

All clothing and accessories throughout by Peter Do

PD I think that’s my struggle with the industry at the moment as well, just the constant search for newness and a constant need to have a new silhouette, new fabrications, a new way of doing things and it’s almost like a game of who screamed the loudest. That’s just not how my brain works, how it operates. I talked about how me and my dad don’t have a lot in common but the one thing that we spend every Sunday doing is making food. He taught me how to make phở. The first few times, you just sort of watch. You don’t try to do something else, you just watch and you emulate and you learn the basic things: the spices, how long it takes, but it’s a lesson in patience. You could pressure cook it, a lot of people do not have time anymore. I feel like pressure cooking phở is such an interesting Vietnamese-American way because you assemble it in a new way working where it’s like this constant hustle and you take care of your family. In Vietnam, you just put it in a pot and you leave it there for a very long time. You don’t even eat it that day, you eat the next day preferably. My dad was like, “We’re not going to eat it tonight.“

OV Yeah, ngày mai ngon hơn.

PD Yeah, ngày mai ngon hơn. So he always just said, “We’re not going to eat it but we’re going to spend three to four hours making this on Saturday morning.“ So Sunday, we wake up, we’re going to enjoy this bowl of phở. Good things take time.

OV And the investment in a futurity.

PD Yes.

OV The promise that ’It’s not even for now but that we will make it towards the goodness ahead’ is so incredible. Wow. I thought about that a lot as a writer. I write one book of poems, and immediately my peers and my teachers say, “You did that, now what are you going to do?“ There’s this kind of demand that, because you’ve written about diaspora, about refugees, about American politics, that you’ve somehow exhausted those themes with one book, and you must now do something else. There’s this idea that one’s obsessions should be commodified into finitudes. We see this all the time in the grocery store. “Now better tasting. Now brand new packaging.“ So I resist this pressure for “newness“ or “moving on“ in my work, because I think to replicate oneself is to kind of cheapen oneself into a product.

PD It’s a very kho struggle, for sure.

OV Our upbringings are quite different, because you came to the States at fourteen. That’s a whole childhood, pretty much, in Vietnam. When I went back to my village in Go Cong, I did not have a Vietnamese childhood in Vietnam, and I’m curious, what was it like for you to arrive in Philadelphia? What does Philadelphia mean to you, particularly the Vietnamese community there? Being Asian on the East Coast is much more esoteric and seldom defined than the more culturally legible West Coast Asians.

PD When I first arrived to Philadelphia, everything was a shock. I wasn’t really aware that the West Coast was the epicenter. I had no idea.

OV Me neither.

PD When I moved over here, my dad passed away when I was in tenth grade, so I only had a year and a half with him.

OV Fifteen?

PD Yeah, I was fifteen.

OV Your dad was here first?

PD Yeah, my dad was here first. My parents were here first and then they brought us over after so I grew up with my grandma. I have a really close relationship with her. Me and my brother were close because of that, because we became each other’s parents and I had to grow up really fast. When I came over here, when he passed away, my mom become a single mother. She runs her own nail salon now, because it was both of them.

OV Your mom did nails, too?

PD Yeah, she has a nail salon, and my dad just left us with that. Then she had to become a single mom with this nail business to do and there’s taxes. I remember doing taxes, like stapling receipts. It was terrible.

OV Oh my god. The first time I did my mom’s taxes, I looked at her gross salary: twenty-four grand. I had no idea. I turned to her and said, “How did you do this?“ Trời ơi. We talked about the magic of fashion, the magic of language. But to me what she was doing was magic. How did she raise me and my brother on twenty-four grand? When you talk about your original idea of fashion and clothing as reparative, to fix, as a site of care, I think that I can see that in how your company works and how you create and how you foster this collective of Asian-Americans, like [Peter Do art director An Nguyen,] and I can see it through and through. Maybe it’s something only a fellow Vietnamese person can see, whereas someone else might recognize it as just “Oh, it’s another hip fashion label.“ But I think if you look closely, in how it operates, if you know what you’re looking for, it’s evident. You don’t have to even explain that. I think that the idea of care is a foundation. You’re talking to me—even the way you’re talking about the shoes, “This shoe line can’t be finished as is. We have to have a rubber one so people won’t slip; we have to think about the body’s limits.“ I think that’s what I really admire about how you’re talking about your work. I’m not a fashion expert. But I really love that you’ve taken everything you’ve been given and went through in your life and put it into your work, into your vision. I think that’s a wonderful way to think about what you aspire to. Would you agree that ultimately, regardless of where the company goes, and where your æsthetic grows, it’s the foundation of care?

PD I care about the people that wear the clothes. I feel the responsibility when I put out something that it’s made to last. I really feel that. I don’t want to create things just for the sake of creating. I feel like that’s something that I do anyway, for myself. I’m constantly creating, but I feel like when it involves people spending their hard-earned money to purchase something that you create, there’s a responsibility in that. I’m asking the clothes to do a lot for the person, for the customer that wears it. I’m looking for those pieces that become heirlooms that can be passed down.

OV The blazer.

PD Yeah, the blazer. The thing that you can pass around. I’m searching for that.

OV In ten years, maybe more Vietnamese children will be wearing Peter Do with their birthday cake.

Archival Polaroids courtesy of Peter Do

PD I’m looking for heirlooms. I’m looking for things that you don’t discard. This idea of sustainability in fashion is something that’s so ingrained in Vietnamese culture. We wash, we don’t throw anything out. Everything is reused. Every bottle in the fridge is like, ’It’s not soda, it’s fish sauce.’ Every bin is sewing supplies, my grandma kept everything. My mom now too, actually, when she comes to visit she’s recycling things.

OV Right.

PD I find comfort in these conversations that I have with my mom now because I feel like we connect in a different way where I understand her struggle. Because now I have a business, I understand how difficult it is for her. While I was struggling to find myself in America as a teenager with my sexuality, with the language, with becoming my own person, my mom was doing all this stuff. I felt like it was such a lonely journey for her as well. I feel that right now. Even though I have a team, it feels like leading is such a lonely journey. It’s really hard to talk about—the things that you have to do, the sacrifices you have to make. It feels like that’s the journey I’m on as well, where yes, I want to be an artist, I want to make things but I feel at the end of the day I believe in a beautiful product that has values, that has functions, and can be somewhat helpful to people. Otherwise, I don’t know why I would do it. Because I don’t just create things for the sake of it.

OV Có đạo đức, or to know that way, or the ethics. And I think that’s how I was raised as well. “Có đạo đức,“ I hear this in the Buddhist temple, when I go to the temple. There’s this idea that there’s a sort of somberness, and somberness is a kind of respect. My mother would say, “Con phai có đạo đức,“ and I started to carry this into my work. When I give my lectures, I lower my voice, and it’s the equivalent of taking your shoes off before you go to the temple or you go to someone’s house. How do I take the shoes off of my voice? I hear that in your work, how do I put forth the treasure and not the self? I think that’s what our idea of integrity is, that it has to speak for itself. I remember when I was finally strong enough, fourteen, to wake up early to shovel the snow for my mom so she can go to the nail salon. I think this is a quintessential metaphor for Asian-American life on the East Coast, where you have to wake up early and do labor to free your car from weather so that you can go into it and do more labor.

PD Yeah, I have similar experiences. That’s one thing that’s very different from growing up in a rice field. I don’t know about you, but I was really looking forward to snow until I had it. I was like, “Actually, I don’t want this.“ I mean it’s beautiful.

OV Beautiful for a couple hours.

PD A couple of hours! I remember getting stuck in a snowstorm with my dad. He parked his car in a strange place while we went to get groceries and then it was towed away. There was a snowstorm and we had to walk for miles to go to the shop to get the car back. That was my first experience with snow. I just remember being really traumatized by it. Before that, I loved snow. But yeah, we wake up early. There’s like a civic duty to do that.

OV Dislodge yourself from the world in order to make a living. It’s such an incredible metaphor. I was also thinking about agency. When I read about you, and I read about how you prefer to stay away from the limelight, turning the face away, behind a mask, I thought it was such an incredible act of agency. Nina Simone used to turn her back on the audience. Sometimes the audiences were majority white and she said, “Well, they’re here for the music. I get to decide where I turn my body.“ So she turned her back to them and they’d get incredibly angry. ’How dare you turn your back around at the supposed center?’ What I’m interested in regarding Asian-American artmaking is: Where does our agency lie? In the American code, the nail salon, the seamstress, the dry cleaner, the maid, the nurse, these labor codes are always in service of something else. My father was a busboy, and all of the labor that America recognizes us is in is the mode of service labor. We’re always opening the door and saying, “After you, madam.“ But to refuse that and say, despite so many of our elders who raised us on that very self-effacing service work, “I’m centering my agency, my imagination, my innovation. I’m a maker.“ We think of the Asian-American prodigy, the music prodigy, the violinist being in service of Bach, Beethoven. Schubert. But the only name in the title is Peter Do. It’s you. Are you conscious of that when you make your work?

PD In particularly the fashion industry, it feels like there’re many instances where I felt I was definitely on the minority side of things. For example, I was thinking this the other day too, my experience at one of the biggest French houses in the world, which is when I moved to Paris when I was twenty-three to work for Céline. I was traveling between London and Paris. That was my first bootcamp, in a way, learning my craft and having this really great opportunity to be here. Definitely my first time seeing a French atelier, where things are made, and it was such an amazing way of working, where people come to work, and they’re proud to be there. It’s not blue collar like here; you’re proud to be a pattern maker, you’re proud to be a technician. You’re proud to be at Dior, Céline, Chanel for fifty years. You were an intern here and you learned your craft, and people are really proud of that. It’s the birthplace of fashion. But I felt comfort in the atelier because there are people that look like me. There are Vietnamese seamstresses that have been there since the refugee days. That was really how I got through my time there, because I didn’t speak French.

OV Thợ may [seamstress]. How we say thợ is a vocation, not just a job. Not đi làm [to work, labor]. Làm is very different from thợ.

PD It’s you contributing to the craft. You have ideas. You have your touch, and no one else can have that touch. It’s not a sweatshop. You don’t make just scrunchies and t-shirts in bulk. You do the invisible work that no one sees—the foundation of a coat, the foundation of a dress that holds you up. I felt comfort in the atelier because there were people from Japan, there’s two Vietnamese ladies that took me under their wings, showing me how to press the garment and how to print patterns, how to sew. I learned a lot from them, because we share the same language. And they fell for me, saying, “Cậu bé này không biết tiếng Pháp.“

OV Thấy tội cho bé này qua.

PD But they were proud because there’s finally someone like me, who is a designer on the team. I had to fight to be there but I wasn’t opening doors. Even though people tried to only see me as someone who opened doors. They say, even when you go there and you see, why are all the interns people of color? How come they don’t ever move on from that, even though you work so hard and your work ethic is above and beyond? You come in earlier, you’re the last one to leave, but I think all those things go unnoticed. Because like you said earlier, as you know, people that look like us are usually the ones that provide service.

OV Yeah. ’They don’t need a promotion because that’s where they belong.’ Sometimes they can’t imagine us leading. This is true in academia with professors too. We’re having a reckoning now, in the American academic field, where people of color have been historically maligned to adjuncting or being junior professors and don’t get tenure. We don’t have the same job protection. Because of that lack of presence in the field, I’ve seen my knowledge and my expertise literally be questioned in ways never questioned with my white colleagues. But it’s also not strange to me. It’s not new. I’ve seen it happen with our elders too. I see my mom, she told me, “I have to do the nails perfect the first time because I don’t want them to complain. If I have to fix it, it’ll cost me another thirty minutes and I don’t get any more money for that. So I protect my time by being the best the first time.“ It’s so beautiful to hear you talk about how we have elders everywhere that could take us under their wings. Also, there’s a kind of subterfuge to that, right? There’s a kind of subversion where you’re supposed to just be doing one task, but in fact you are acquiring something wider. When you’ve ceased being a functionary and started being an origin of ideas. Even when they lock you into a task, they can’t lock your imagination. When I was writing my first books, I was working in cafes in the city. I had two jobs to help my mother with her bills and had no time to write during the day. To this day, I write only at night. Past 12 AM is when I usually write, and it’s just a habit now. But back then, that was the only time when I could have the final word of the day. Everything quiet, my phone doesn’t ring.

PD I love that.

OV So all of my books, my three books, I wrote past midnight. That’s just how it always is—but I don’t know how long I can do that.

PD I really felt that, that’s literally my experience. My work is that too, I spent many nights by myself in the atelier because that was the only time that I wasn’t asked to do mundane tasks just to get through the day. When I was in school, the nighttime always made me feel good. Everything’s quiet. I have my own time to really think and do all that stuff. In the day I’m interning or doing schoolwork or working somewhere to make money and things like that. So I really felt that too.

OV Can we talk a bit about [Vietnamese-language variety show] Paris by Night because—

PD We could!

OV It perplexed me at first because I was never asked to watch it. It was like the adults’ relaxation time. We would have Paris by Night bootlegged from tape to tape to the point where the film was so worn and warped. You go to the local Viet grocery store to get the tape. Sometimes it’s like our own Blockbuster. So when it comes out, everyone, the whole community was like, “Don’t talk to me. I’m not cooking tonight.“ Every time Paris by Night came out my mother would get us McDonald’s and tell us to leave her alone. So the show was always on the side to me. But when I would peek at it, I was just so stunned by the beauty of it all. I think we were one of the few diasporas that, in a very short time, twenty years, less than twenty years, not only established a culture, wide-ranging communities, but also a media company. We fashioned an entire entertainment industry as refugees and one function of that project was to center beauty. Regardless whether you speak Vietnamese or you know what’s going on in Paris by Night, you look at it at any given time and it’s just extravagant beauty—an outpouring and this meticulous care, from the plays to the performances to the awards to the glittering ao dai. I remember looking at my first Paris by Night and saying, “Wow, it’s like stars. We’ve made ourselves stars.“ What was it like for you watching Paris by Night?

PD Oh my god, I just remember it being really glamorous. I feel it was just so glam. It’s Vietnamese-Americans just dressed up and thriving. In that world, like you say, we’re the stars. You don’t see that, you don’t see your representation in the Oscars or the Grammys, or things like that, so I felt like that was an Oscar, a Grammy. You watch these things, because I remember the Oscars growing up, or the Grammys, that was not something that we were watching. Now we have our community in there and they have been recognized for their talents and crafts. Now we participate, but before that, you just didn’t think that was possible. It’s just like before, for example, Humberto and Carol at Kenzo opened, I didn’t know that you could be a director at a French house, you couldn’t do that. I remember, because Kenzo was next to Céline, the atelier. I remember just being outside and seeing them next door, just smoking or talking to the team, and I was like, “It is possible, even though I don’t know who they are.“ Years later, we became friends. We had a conversation like this for Interview Magazine, and I told them that. I told them that even though they were just doing their thing, it opened doors for people like me who look next door and see that it is possible, while I was getting coffee and things like that, getting lunch. There would be one day where I would get here because they opened that door for me, even though they didn’t know it. They were just doing their thing. So for me, these representations matter in that way where it’s little things that sort of hack a switch in your brain. Once you see someone doing it that looks like you—it’s really hard to be that trailblazer. You don’t even know where to begin.

OV So lonely.

PD Yeah, so now when I have opportunities from these big companies it’s always a surreal moment. Those are the moments when I get hit back to reality where, “Wow, okay, I am in the conversation, I’m in the room. Now I made it. I stepped into the door, I’m in the room.“

OV You’re not holding the door anymore.

PD Yeah, and the door is kind of open. Once you’re in, I always think you opened the door or you left it open for other people to come as well. That’s the kind of responsibility that I feel sometimes. No, I don’t have to do it but I feel like other people opened the door for me. And I feel like I need to leave it open once I enter into another room.

OV Yeah, that’s so beautiful. That’s how I see teaching. I never imagined being a professor. I donʼt even know how to say it in Vietnamese. I just learned the word for professor, giáo sư, like two years ago. But now I’m seeing versions of myself in my classroom. I’m seeing young Vietnamese writers and the idea that, “Oh, even when I didn’t imagine this, it was already there.“ They were always headed this way. It’s such a touching moment. It’s also freaky, because I was like, “Oh my god, I’m anh. I’ve never been anybody’s anh!“ As long as I’m not a chú. I want to touch on this idea of imposter syndrome that so many of us experience. It’s an interesting word, because it’s a pathology, an illness. It troubled me for a long time. I think when you said that there was a breakthrough for you when you started to see that, “Oh, I can make something for myself.“ I had a similar thought when I said, “Wait a minute. My imposter syndrome is actually my strength. I don’t ever want to be comfortable in positions of power.“ The day that I’m comfortable in these large institutions, in these reified ivory towers, is my death. So I am an impostor, it was never meant for me. They didn’t imagine me when they built these sites of power. May I always be an imposter. My imposter syndrome is my strength because it gives me vigilance, discernment, awareness, and fruitful doubt. My mother used to say, “You can tell everything by how they look at you.“ So I started to see this as my tool, my asset, and I don’t want to lose that. I think the great work that we do is to turn an imposter syndrome that it started out as into a kind of immune system that protects us. I don’t know if I feel at home anywhere. But I realized that the idea of the imposter is such a beautiful idea, the idea that someone can disguise and sneak in the back door with their head down and just do the threading work and then one day, put their head up and there’s a fashion house or a book under their name. It reminds me of when you talk about repair and recycling, it reminds me of when the French and the American occupational forces left Vietnam, and we would cut the tires off of military vehicles and make sandals because the rubber was so strong. The strength and innovation of a military meant to destroy us was salvaged into footwear.

PD It’s a fashion statement now.

OV I love that innovation of taking what was supposed to annihilate you and recognizing its strength for other purposes. To say, “Oh, those military tires are very strong and I’m going to put it on my feet to go to school.“ I wonder about that, how do you navigate that idea of imposter syndrome?

PD That’s like the tagline. I have a problem with taglines. These very loaded taglines. It’s like, “Peter Do is making the suit of the moment. Peter Do is the next great designer. Oh, Peter.“ I have an issue with this clickbait thing that’s just like, “Oh my god, that’s a big statement.“ That’s a big statement from this ten-question interview that you got out of it.

OV And it’s not always true. Like my first profile, I was twenty-five or so, and the tagline was, “Ocean Vuong wants to fix the English language.“ But I never said that. I talked to the reporter for three hours and never said that. And I got all this hate mail from people saying, “How dare you think English should be fixed! Go back to your country!“

PD Oh my god, that is so crazy.

OV Right? It was meant to be positive, provocative. How Ocean Vuong is going to fix the English language? But I never thought that. I want to trouble the language, yes, but I don’t think any language needs to be fixed. It means something to me, on a philosophical level, to control how a Vietnamese-American is perceived or not perceived or denied. One of my favorite words now is no. And I had to learn how to say no, because our parents could hardly ever say no. You can’t say no to a customer. You close at 9 PM, they walk in at 8:50, and you have to say yes to a 45-minute pedicure.

PD You have to say yes. I really feel that. No, it’s true. I think learning to say no is one of the things that I’m learning too. It doesn’t come as easily. I feel like I’m at the crossroads of so many different things. I’m being pulled in many different directions all the time. As a business owner, because it’s my name on the door, also. I feel like my face is the only thing I have left in a way. I feel like that’s the only thing I have left that I have for myself. You gave so much, you give your story. My upbringing turned into this collection, my love for this turned into these collections. My obsession with something, my favorite movie, it’s being dissected. Everything that I love and care about is being commercialized and turned into something else that we can sell as a story to make this collection sell better to buyers, to add more value to my work, things like that. I’m constantly struggling with it. I just want to make a product that’s just enough—you don’t need embellishment, you don’t need all of it. You don’t need all of these crystal paillettes, these things that you need to put on a blazer to sell it, because the foundation is enough.

OV It turns into an autopsy.

PD Exactly.

OV The desire to understand someone that very quickly becomes an autopsy where everything is weighed against the living personhood. It’s kind of vampiric, sinister. I think your protection of that is absolutely vital. I’m so happy to hear that and that you’ve been able to do it. It’ll be a lifelong struggle. It’s important to say, “You get the work, but you don’t get the person.“ My job, for example, is to talk. I traffic in ideas and stories, so when I go in front of the camera, the interview, I have to deny things that people want to know about me and my family—which is why I could never write a memoir. The foundation of my novel, the context, is true, Vietnamese family in Connecticut, but the characters there, I don’t know them. They exist in the book. They all have been transformed. I think that’s how I protect myself, through changing the work.

PD We have to keep something for ourselves, I think. I try to. But like you say, it is getting more and more difficult as the brand grows bigger. And there’s more. Now I have contracts where people, they actually put in there I’m required to go to this party for at least three hours because they know that I won’t show up. So they know. You gave me so much comfort, honestly. I feel so inspired by your story and by these conversations. I feel a little bit less lonely, for sure. Knowing that there’s others out there who also feel the same as me and have this similar experience gives me that comfort to keep going.

OV It’s an honor—and we’re only at the beginning.

For more information, please visit PeterDo.net. Read this story and many more in print by ordering our sixth issue with a limited edition Book Tank designed by Do here. Do has selected CAAAV, which works to develop leadership in the working-class Asian immigrant community, as the recipient of proceeds from direct sales of his cover of CERO06.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.