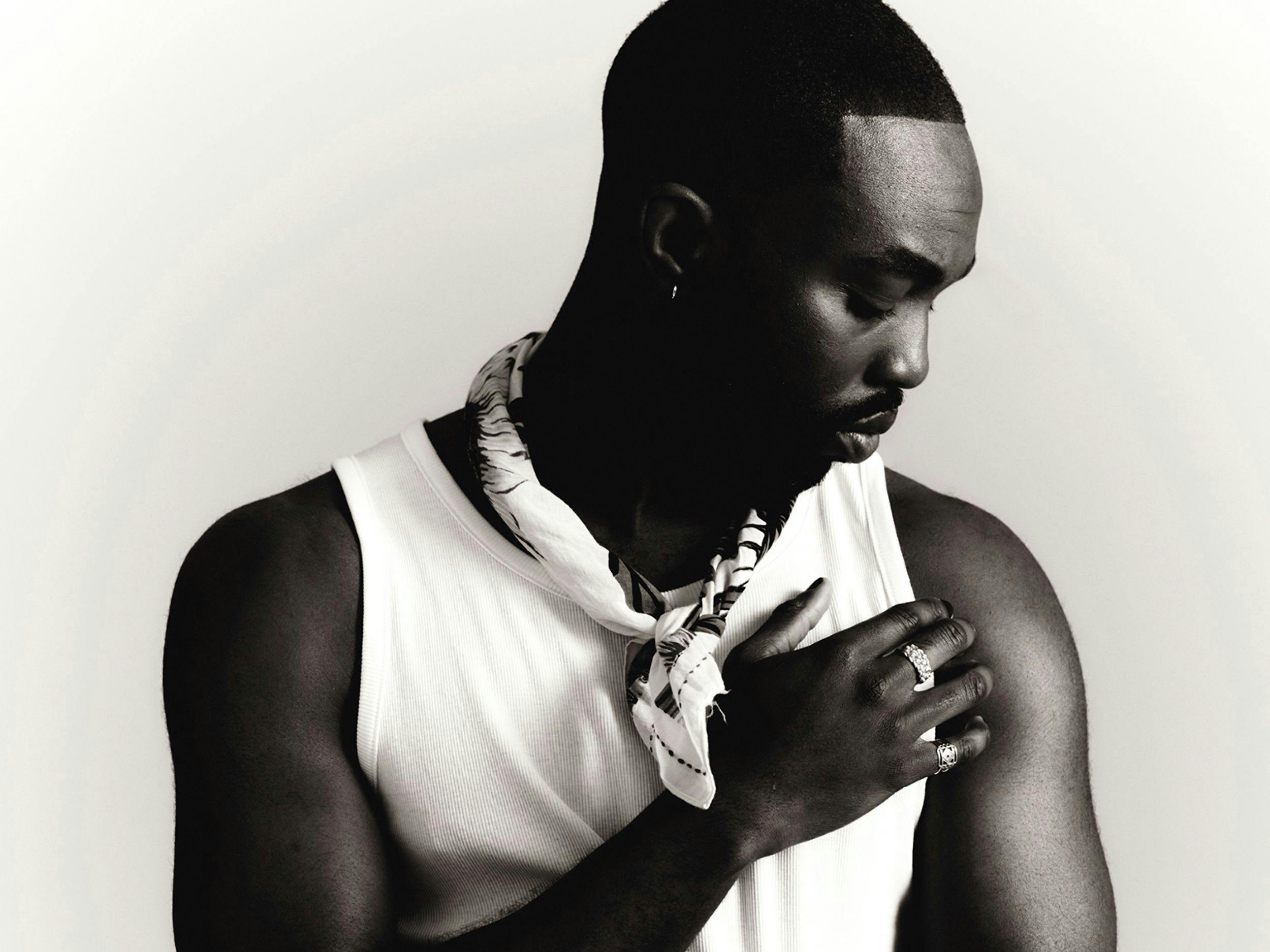

Critical Voices: Olayemi Olurin

Since Olayemi Olurin was a little girl, her grandmother told her she would become a lawyer. “It was my life plan,“ she says of her longtime aspirations. Now, at thirty years old, Olurin has practiced law in New York City for five years and uses her social media accounts to share ongoing abolitionist critiques of the carceral system that disproportionately imprisons Black and brown people, grounded in her experience as a public defender. A “movement lawyer,“ as Olurin describes herself, she began her career by providing legal representation for low-income New Yorkers caught up in the criminal legal system, all while advocating for the abolition of police and prisons.

Born in the Bahamas, Olurin moved to the United States for high school in order to set herself on the track for law school. “The law controls everything. The reason I have a window in this room is not because they want to but because the law means they have to,“ she explains of housing law, for example. “So I realized if the law is always interacting with me, I want to interact with it.“

Olurin was in law school during the Ferguson, Missouri, protests spurred by the police killing of Michael Brown. She already hated attending St. John’s, where most of her classmates would become prosecutors. She was writing her thesis, “Colored Bodies Matter,“ on the relationship between bodies and power when her advisor, Dr. Kathleen Sullivan, referred her to abolitionist literature, fueling her interest in becoming a public defender. Angela Davis’s “Are Prisons Obsolete?“, a foundational abolitionist text that often serves as an introduction to the political framework for those who aim to see prisons and police abolished, shifted Olurin’s understanding of her approach—and her relationship—to the law and courts. “People tend to think you become a public defender because what you do without that money you would make up for in personal emotional fulfillment or feeling like you’re doing God’s work,“ she says. Historically, public defenders have been so underpaid and overworked that many in New York have recently struck for better contracts and working conditions. “You’re not doing God’s work. You’re a harm reductionist.“ The limitations of the law, she explains, mean it cannot be used as a tool for liberation.

Indeed, the work of public defenders is ultimately to defend poor people accused of a ’crime,’ which is defined by the state and is not necessarily always violent or causing harm. As Olurin regularly reminds her one-hundred-and-thirty-thousand-and-climbing Twitter followers, a majority of the people she defends are accused of what are known as “crimes of poverty“ like stealing, panhandling, or being unhoused and sleeping on the streets. Historically, over eighty percent of people held in Rikers Island, the notoriously brutally violent jail where nineteen incarcerated individuals died in 2021 alone, have not been convicted of a crime but are simply too poor to post bail.

What makes Olurin’s abolitionist musings on social media stand out is her ability to quickly and succinctly explain typically complex or not commonly understood legal concepts to non-lawyers via tweets and livestreams. “That’s another way that helps me translate to people more effectively. My friends and the people in my life tell me what stands out to them as people not in this work,“ Olurin shares. “My mom was the person who said to me, ’Rikers is pretrial? Emphasize that. Emphasize it, emphasize it. Because I didn’t know that.’“

Over the last few years, Olurin’s platforms have grown as she has gained notoriety for her quick critiques of government officials for their approach to public safety and incarceration. During the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, then-New York governor Andrew Cuomo, who later resigned in disgrace due to allegations of sexual harassment, made rollbacks to recently passed progressive reforms to bail. Olurin took to Twitter to advocate against the changes, and her follower count quickly grew. Since then, she has kept watch on Mayor Eric Adams, a former police officer who aggressively supports the NYPD, fact-checking his administration in real time on crime stats and raising awareness on the evils of Rikers Island. “Importantly, the safest communities are not the most policed—they’re the most resourced,“ Olurin says. “The first thing we need to do when we start to talk about alternatives to these things is we have to recognize that prisons and policing are not there to do that. They’re not there to address harm, they’re not there to address or solve crime.“

Police actually spend the vast majority of their time responding to non-criminal issues like noise complaints or traffic violations. When a ’crime’ occurs, police respond after the fact and generally only make an arrest in about eleven percent of reported crimes. As an alternative, Olurin echoes abolitionists’ pragmatic approach of redistributing resources and shifting our collective approach to public safety away from police and prisons to things people need that can prevent violence, like housing, healthcare, and employment. “Abolition is a vision of tomorrow. It’s a vision of the future,“ Olurin adds. “We understand that they’re not going to close all the prisons and all the courts and everything today, but what we’re trying to get people to understand is, you continue to invest in mass incarceration, in this prison industrial complex that does nothing. It’s a system of slavery, and it’s there to make money.“ If the goal is to address harm, policing does not work.

Olurin is fluent in breaking down the legalese and, despite being a lawyer, is media-trained and press-friendly. After five years as a public defender, she’s accepted a position as director of media advocacy at Zealous, where she’ll work on uplifting other activists, attorneys, and organizers and connecting them with media opportunities, helping to bring in others to the work of disrupting the dominant narrative that believes the police are a foundational part of society and not an institution that can and should be abolished.

Read this story and many more in print by ordering our sixth issue here.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.