Nathan Law Is Paving His Way Home

Last spring, when rumors of a new national security law to be imposed by the Chinese Communist Party began to circulate in Hong Kong, Nathan Law knew he had a decision to make. As one of the city’s leading pro-democracy activists who had already been jailed once for his role in the 2014 Umbrella Movement, Law recognized that the provisions, including one that made subversion against the authoritarian government in Beijing punishable by imprisonment for life, presented a direct threat to him and the work to which he has dedicated himself for the past several years. Ever since taking control of Hong Kong in 1997 after over one hundred and fifty years of British rule, China has forcefully and consistently tightened its vise grip over the “special administrative region,“ despite an agreement in place to adhere to the principle of “one country, two systems.“ The populous island city was meant to be officially part of China while being allowed to maintain the freedoms it had enjoyed beforehand, many of which have never been experienced on the mainland. As the details of the legislation coalesced and loomed more threateningly, Law urgently considered his next move, a dilemma that had taken on existential gravity. “The question of whether I should leave popped up in my head because I felt a strong sense that the international advocacy we had been doing was not going to continue after the national security law, at least not in Hong Kong,“ he explains. “People remaining in Hong Kong would be silenced, so I felt like we needed a recognizable figure to be speaking up for Hong Kong and to continue the international advocacy work, urging the international community to hold China accountable, to sanction the government officials who are responsible for these human rights violations. I had a think on it and I believed that I am a suitable person for doing so.“ Days later, he departed the city into exile.

Now living in London, where he has been granted asylum by the British government, the 27-year-old remains resolute about his decision, despite having had to sever ties with his family and friends who still live in Hong Kong for their protection. After coming to prominence as a student leader during the 2014 protests against electoral restrictions, co-founding a new political party, serving as Hong Kong’s youngest-ever legislator until his election was overturned by the Beijing government, and then being imprisoned for two-and-a-half months, his stature as a leader of the international fight for democracy has only grown over the past year. Last September, Time Magazine readers voted him the most influential person of 2020, edging out Joe Biden, Billie Eilish, Meghan Markle, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Many of his fellow pro-democracy activists were arrested last fall, leaving him as one of the few voices able to champion Hong Kong on the world stage. “After I left, I felt a larger responsibility and obligation to speak up for the Hong Kong people because those who couldn’t leave, those who are behind bars—we are actually pursuing the same goal,“ he says. “They are suffering more than I am and most of them are my friends. We talked about things, we campaigned together, we’ve got strong bonds. Their suffering in the cell actually is my motivation for my advocacy work.“

Growing up in Hong Kong as the son of a construction worker and a street cleaner, Law was taught by his parents, both immigrants from China, that “politics is not something that ordinary people like us should be involved in,“ he recalls. Having lived through the political and societal upheaval of the Cultural Revolution, they viewed the government as dangerous and corrupt and the Chinese Communist Party as an insurmountable oppressor. After moving to Hong Kong from Shenzhen with his mother and two brothers at the age of six to reunite with his father, Law attended pro-Beijing schools where the party line was unquestioningly parroted. It was only in 2010, when the Chinese writer, activist, and political prisoner Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize and was denounced by Law’s school principal the next day, that Law began to seek out alternate perspectives. “The only thought that I had is, when you are a Nobel laureate, you should excel in certain aspects, so how come such a recognized person was being criticized so heavily?“ he recalls. “It actually triggered my curiosity and I looked into what Liu Xiaobo had been doing and his philosophy, so it opened a gate for me to understand more about his advocacy and the concept of human rights.“

Law went on to attend Lingnan University, where he was elected chairman of the students’ union in 2014, laying the foundation for his eventual role as a student leader of the Umbrella Movement later that fall. “I already had a feeling that I was going to be involved in social movements because that is the way that we could change society: by our participation,“ he says. “I saw myself, as a college student, like a half intellectual. We don’t really have family burdens or expectations on our shoulders because we’re still students, but we’re learning about how we could create a better society and what it would be like in a better world. I think it’s actually the greatest time to be involved in social movements because we’ve got that knowledge, we don’t have that burden, and we’re energetic.“ That September, when students began to strike against proposed reforms that would effectively have allowed the Chinese Communist Party to pre-screen candidates for Hong Kong’s highest office, Law quickly found a place on the front lines, participating alongside four other student representatives in a televised debate with government officials. He also took a leadership role in the campaign, which occupied a number of the city’s central districts for seventy-seven days and, coming after the Arab Spring and Occupy Wall Street, was one of the major grassroots movements that helped shape the course of international protest over the last decade. For Hong Kong, a city that had long prided itself on its adherence to law and order, the act of civil disobedience in itself was a relatively new development; at a scale that at times encompassed a hundred thousand people, the effect was momentous and, as Law describes it, “a breakthrough in Hong Kong’s history.“

Amid increasing police violence and declining public support, the Umbrella Movement eventually disbanded, and Law returned to his studies. In 2016, he co-founded the new pro-democracy political party Demosisto with fellow student activists Joshua Wong and Agnes Chow (both of whom have now been in prison since last December) and declared his candidacy for Hong Kong’s Legislative Council, eventually becoming the youngest person ever to serve on that body. “In Hong Kong, the only driving power to change has always been on the streets instead of in the chamber, but I also feel like if you want to magnify the influence of yourself and your organization, then you must have a constant impact on the political discourse,“ he reasons, “so being involved in council politics is actually something that could enhance your impact in social movements.“ Around nine months later, he was removed from office after the government in Beijing issued a new decree retroactively deeming his oath ceremony illegitimate—a blatant, aggressive, and unprecedented intervention into local politics that negated what Law calls “likely the last free election that Hong Kong could have.“

From there, the situation deteriorated rapidly. In 2017, Law was sentenced to several months in prison alongside his close friend Wong and another activist, Alex Chow, before all three were released the following February. When Hong Kongers began gathering in March of 2019 to protest a proposed law allowing extradition to China with its corrupt judicial system, Law became heavily involved but says there was a conscious decision to position the movement as leaderless to prevent the government from stamping out the protests by persecuting a few key individuals. Millions of people participated, sometimes clashing violently with police and occupying city streets, universities, the Legislative Council, and even the international airport. Law says that, just five years after the Umbrella Movement, the mood had changed entirely. “Once I heard an analogy of the difference of the two protests: In 2014 in the Umbrella Movement, we saw hope on the streets, but in 2019 in the anti-extradition movement, we saw desperation,“ he elaborates. “I think it really reflects a certain change of mentality where a lot of Hong Kong people felt like in 2019 it was their last battle. Emotionally, they felt an urgency in coming out to reject the erosion of freedom and that infiltration from China and the attacks from China on our system. They were actually quite hopeless about Hong Kong’s situation under the Chinese Communist Party regime.“ Local elections that November saw record voter turnout and resulted in landslide victories for pro-democracy parties.

The protests began to peter out through the beginning of 2020 before coming to a stop as Covid-19 forced the city to lock down, picking up again later that spring after the new national security law was announced. For Law, the latest developments in Hong Kong comprise only one of the more obvious facets of a widespread slide away from democracy in recent years, which can be seen across the world in countries as varied as Turkey, Hungary, Brazil, and the United States. The trend, he adds, is one of the most troubling developments the international community faces today and can only be turned back through concerted, collective effort. “We have to see democratic decline as a global problem, like climate emergencies and public health crises. People die in the hands of tyrannies, people die when they are poorly treated in protests,“ he argues. “There is a tendency of treating democratic decline as an individual problem. Authoritarians can really disguise their human rights violations in the name of sovereignty and internal affairs. Democratic countries are not willing to be united and push forward and say that when you kill these citizens in your country, when you deprive their individual rights, that is violating international norms and violating these people’s basic rights and dignity. We have to step up and deploy appropriate measures because if the international community does not act, no one is holding these people accountable.“

Even in America, which prides itself as the world’s most robust democracy, the events of the last four years under former President Donald Trump, from persistent attacks on the independent media to the gradual erosion of voting rights— culminating in the January 6 insurrection at the Capitol—have demonstrated just how fragile our system is, a lesson that Law says is necessary to keep constantly in mind, even in ostensibly open societies the world over. “Especially for our generation, we usually forget how difficult the process of fighting for freedom and establishing a free and fair political system was,“ he says. “That is actually very reasonable because we didn’t go through that time. I believe that in Hong Kong, if there weren’t protests in 2014 and 2019, a lot of people would be complacent about the system. They wouldn’t really feel like they have to commit and they have to fight for the protection of freedom or fundamental rights.“

To counteract that complacency, Law is currently at work on his first English-language book, Freedom: How We Lose It, And How We Fight Back, to be published this November. Using Hong Kong as a lens to frame anti-democratic movements around the globe, the book will “remind the people who are living in democracies not to take freedom for granted,“ he explains. “We bear the responsibility to be vigilant against the erosion of freedom and to be the guardians of it. Our democracies have been threatened constantly and similarly the awareness of how precious freedom is is actually dropping,“ he adds. “There are a lot of research and polls showing that generations born in the free world lack a certain awareness of its importance and the constant intimidation that we receive.“

Law may still be settling into his new homeland, but the work and the struggle continue without pause. The day after arriving in London, he testified over video before the United States Congress about the need for international action to censure China for its human rights abuses, not only in Hong Kong but against ethnic and religious minorities in Tibet and Xinjiang. He published an op-ed in the Guardian last December about his decision to settle in the United Kingdom to focus his advocacy work there and in the European Union, which he described as weaker than America in its commitment to standing up to the Chinese Communist Party. His greatest responsibility, though, is to never give up. “As an activist, I always believe that I’m not entitled to lose hope because my duty is to empower people to believe in freedom and the democratic system as a better system to represent people and hold the government accountable. From the bottom of my heart, even with how desperate the reality is, I have a certain hope in people,“ he says. “There will be changes definitely. We don’t know where the changes will lead us, but at least when there is a possibility to change, that means hope. I’m not a blindly optimistic person but I don’t feel like we have to lose all hope or feel like there’s only desperation without light at the end of the tunnel. That’s what we should do and continue to do our work no matter what positions we’re in.“

A few years ago, the Bulgarian author Maria Popova wrote, “Critical thinking without hope is cynicism. Hope without critical thinking is naïveté.“ As disheartening as the current situation in Hong Kong may seem, Law has managed to find his way to a sort of equilibrium by confronting the present with clear eyes while looking to the future with a full heart. “Realistically speaking, change is not going to happen in a few years,“ he admits wistfully. “There will be a long uphill battle that we as Hong Kongers have to overcome and for me, it may take decades to go back to Hong Kong, but for now, what I’m doing is paving my way home.“

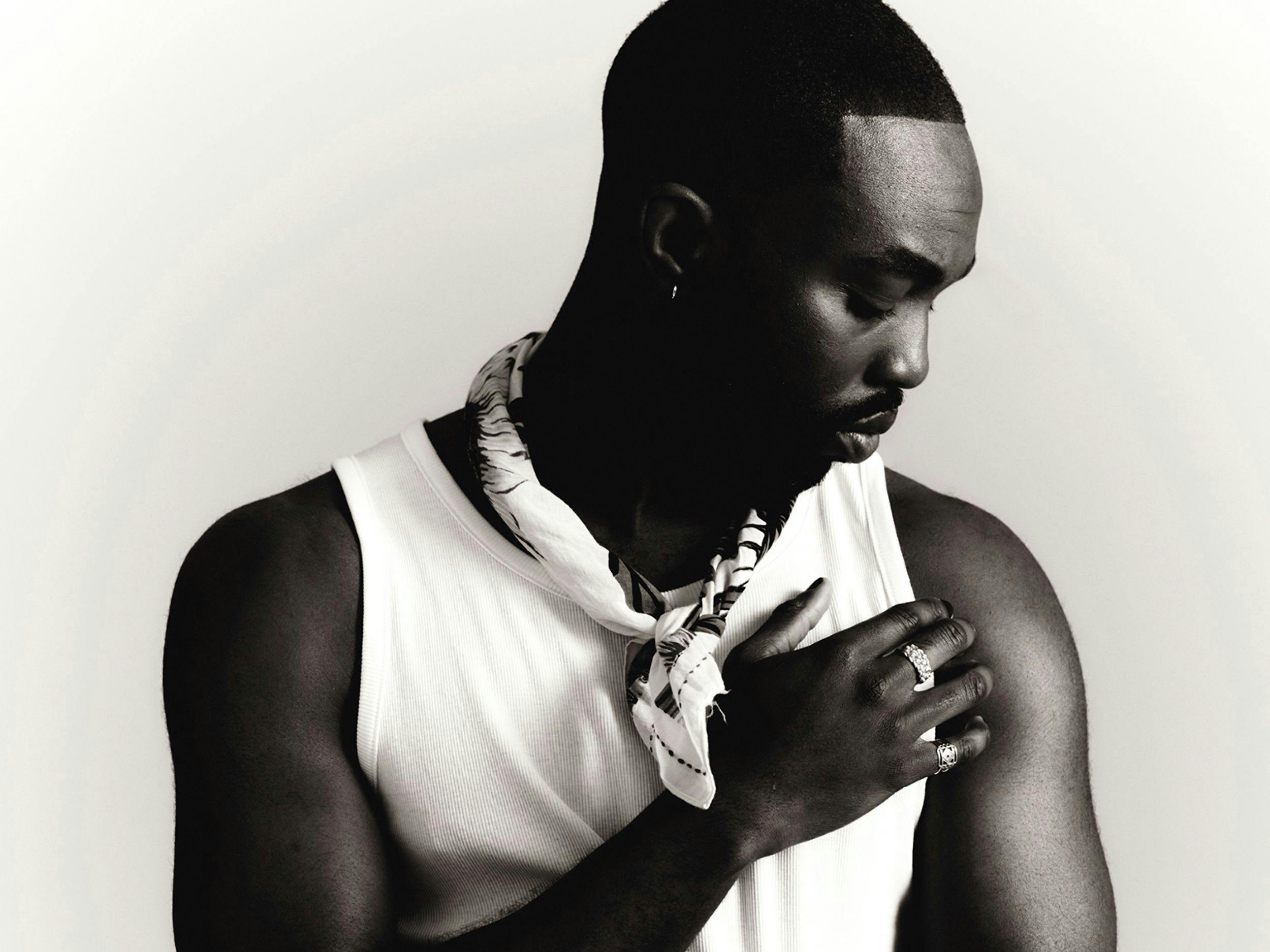

Read this story and many more in print by ordering our inaugural issue here, with all net proceeds from Law’s cover going to the Hong Kong Assistance and Resettlement Community.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.