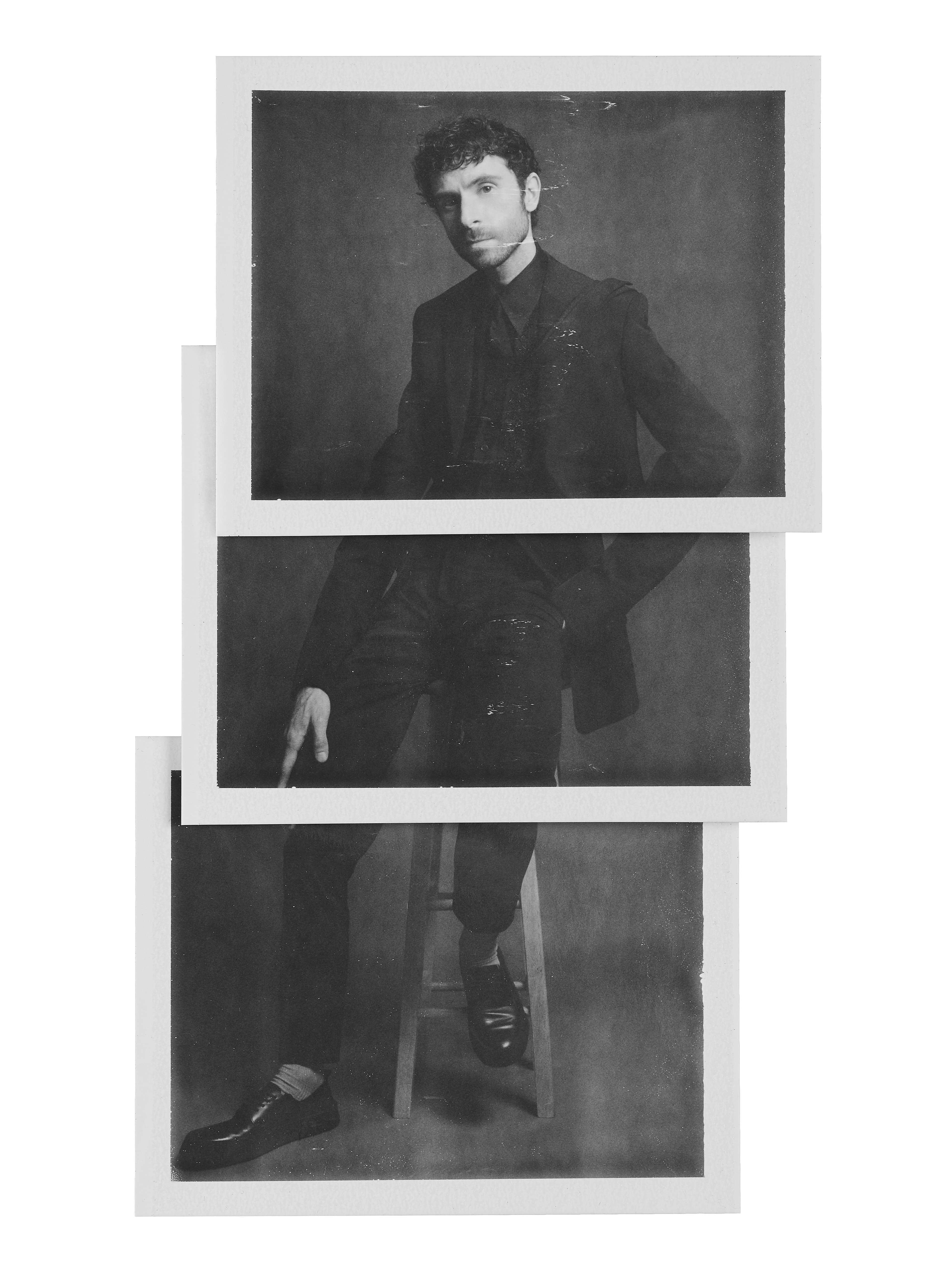

Vintage suit by Prada from the David Casavant Archive. Vintage shirt by Versace from the David Casavant Archive. Vintage tie by Raf Simons from the David Casavant Archive. Socks by Comme Si. Shoes by Ami Paris.

Live from New York: Matthew Aucoin

Born to Apollo, god of the arts, and Calliope, goddess of poetry, Orpheus was, in the Ancient Greek tradition, a bard who created music of such beauty that even stones were stirred by the sound. His most legendary exploit, a trip to save his wife Eurydice from the Underworld, came to an unfortunate end when, overcome with doubt, he violated Hades’s condition not to turn around and look at her during their return to the world of the living, banishing her forever to a second death. The myth has inspired painters like Titian and Rubens, poets like Rilke, and directors like Cocteau and Céline Sciamma, but it is no surprise that composers have been particularly drawn to the story, in a long tradition stretching from Jacopo Peri’s 1600 work Euridice, the earliest opera still surviving today, to Matthew Aucoin’s Eurydice, which made its Metropolitan Opera début last year.

For his version, Aucoin partnered with Sarah Ruhl, who adapted her own evocative 2003 play for the libretto. Recasting the myth from the perspective of Eurydice, Ruhl embedded the story with an underpinning of grief, inventing the character of Eurydice’s recently deceased father, who greets her in the Underworld and attempts to comfort, guide, and protect her. In the play’s third movement, Eurydice causes Orpheus to look back at her as they ascend, a crucial change in the narrative. “Most of the adaptations out there don’t engage with the brutality of the myth and what it’s really saying about the relationship between art and life,“ Aucoin says about the play. “I think it actually tells a very pessimistic story about the nature of art making or at least it suggests that some kind of very stark choice has to be made because there is this sense that Eurydice is almost sacrificed at the altar of music itself, which is terrifying. What I loved about Sarah’s take on it is that it is equally brutal in terms of the way the tragedy unfolds, but it shifts both the agency and the blame to Eurydice. You can’t have one without the other. Sarah’s Eurydice is much more nuanced than the figure of Eurydice usually is, but also the tragic flaw is hers in a way. She calls out and language itself is the culprit.“

Along with his first opera, Crossing, which was based on the life of Walt Whitman, Eurydice continues Aucoin’s ongoing investigation with what it means to be an artist. “I think there’s this underlying question of how you relate to the world and what you can bring to the world and whether it’s worthwhile,“ he explains. “Certainly that pervades Crossing and I think Whitman, in spite of his ebullience and optimism, was quite tortured about the question of what his role in society was as an artist and as a queer person. He’s working through this question of like, ’I’m not a soldier, I’m not a straight person who’s going to get married and be fruitful and multiply. What can I do? What can my art do?’“ In Eurydice, Aucoin approaches that question with one degree of separation, offering his title character the bracing line “This is what it is to love an artist,“ sung with a mixture of resignation and resolve. “The question of how do you relate to the world and how do you relate to other people is still very present today,“ he adds.

Sweater and shoes by AMI Paris. Shirt by Bode. Pants by Valentino.

When Aucoin and Ruhl were first introduced several years ago through Andre Bishop, Lincoln Center Theater’s artistic director, for the Met’s commissioning program, they were unfamiliar with each other’s work. Early in their collaboration, she directed a pointed question at him: Can operas be funny? “I remember thinking, ’This is very depressing that she even has to ask the question!’“ he laughs. “We in the opera world have really failed at some essential task.“

It would be hard to imagine a better guide into the world of opera and classical music than Aucoin, who was Los Angeles Opera’s first-ever artist-in-residence from 2016 to 2019, now serves as the co-founder and artistic director of the American Modern Opera Company (AMOC), received a MacArthur “Genius Grant“ in 2018, and recently published a book, The Impossible Art, which urgently and candidly makes a case for the art form’s place in today’s tumultuous culture. Now thirty-two, he is also one of the youngest composers ever to premiere a work on the Met’s main stage and, through his work with AMOC, which became the first interdisciplinary collective to serve as music director for the Ojai Music Festival last month, is one of the leading creative voices expanding the reach of classical music today. “Live performance and performing arts of all kinds need defenders, so it felt like a good time to write down the things that I love about the art form,“ he explains about the pandemic-era impetus to write his first book. “It’s based on this idea that opera is impossible by its basic nature, that it aims for this synthesis of all the human senses and all art forms that is never really achievable, but it’s touching precisely in the ways that it fails.“

Having been celebrated as a prodigy since he began composing at the age of four, Aucoin has had many years to contemplate the life of the artist and the state of contemporary classical music, an art form with a long history, some of it troubling in its inequities, and what many would say is a tenuous position as companies fold and orchestras pare down in the struggle to return from the pandemic shutdown. Still, as part of the Met’s first season back, which began with its belated first opera by a Black composer in September and ended in June with a run of new and recent works, he says he is optimistic for the future. “One thing that is really heartening about the Met season, just as one example, is that I think it’s demonstrating that opera is not just one thing,“ he says. “For Eurydice, we saw a really quite young, I think very theater-savvy audience at many shows. I found myself going, ’Look at these people! Where are they all coming from?’ That to me feels like the right way forward because we tend to talk about the opera as this monolithic thing, as if it’s one brand, one flavor, and you either like it or you don’t. You would never say that about rock music, because are we talking about death metal or are we talking about Belle and Sebastian? So I think the first step is to recognize the multiplicity of this art form and to create pieces and spaces and productions that welcome in the multiple communities.“

Now a year into the return of live performance, as various art forms both attempt to recapture what was lost and pave a new pathway forward, Aucoin, ever the champion of his craft, says he has been heartened by the renewed sense of camaraderie he finds every time he communes with others in a darkened theater. “I’ve missed the feeling of bonding with people through a collective experience,“ he elaborates. “For me, the real value in live performance comes through the way that you can bond with someone, even someone that you barely know, through the act of sharing an experience with them. I think this mysterious thing can happen because a work of art can be a shared inner experience, it’s like an inner experience that is somehow also collective. It makes this kind of bonding possible between people that doesn’t happen on a city street or in a restaurant or in other kinds of spaces. I’ve missed that because I do think that those shared experiences strengthen community bonds in mysterious ways.“

The Impossible Art: Adventures in Opera is out now. See the full Live in New York series here.

Vintage suit by Prada from the David Casavant Archive. Vintage shirt by Versace from the David Casavant Archive. Vintage tie by Raf Simons from the David Casavant Archive. Socks by Comme Si. Shoes by Ami Paris.

Vintage jacket by Prada from the David Casavant Archive. Vintage shirt by Versace from the David Casavant Archive. Vintage tie by Raf Simons from the David Casavant Archive.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.