De Jesús wears all clothing, talent’s own

Herencia: Daniella De Jesús and María-Elena Pombo

The dozens of countries that comprise Latin America stretch over six thousand miles across the Western Hemisphere, from the border city of Tijuana to the southern town of Ushuaia, facing Antarctica. The region’s culture and history are even vaster, with the influence of Indigenous and Pre-Colombian civilizations continuing through centuries of colonization, decades of recent political and economic change, and a newfound flourishing of social justice movements sweeping across the continent. With that rich legacy, Latinx artists are responsible for an abundance of creative variety in film, literature, design, dance, music, fashion, architecture, and the fine arts. As Hispanic Heritage Month comes to a close, photographer Andrés Altamirano and stylist Carolina Orrico share a project celebrating six such talents, reflecting the breadth and depth of the herencia—or inheritance—that informs their work today.

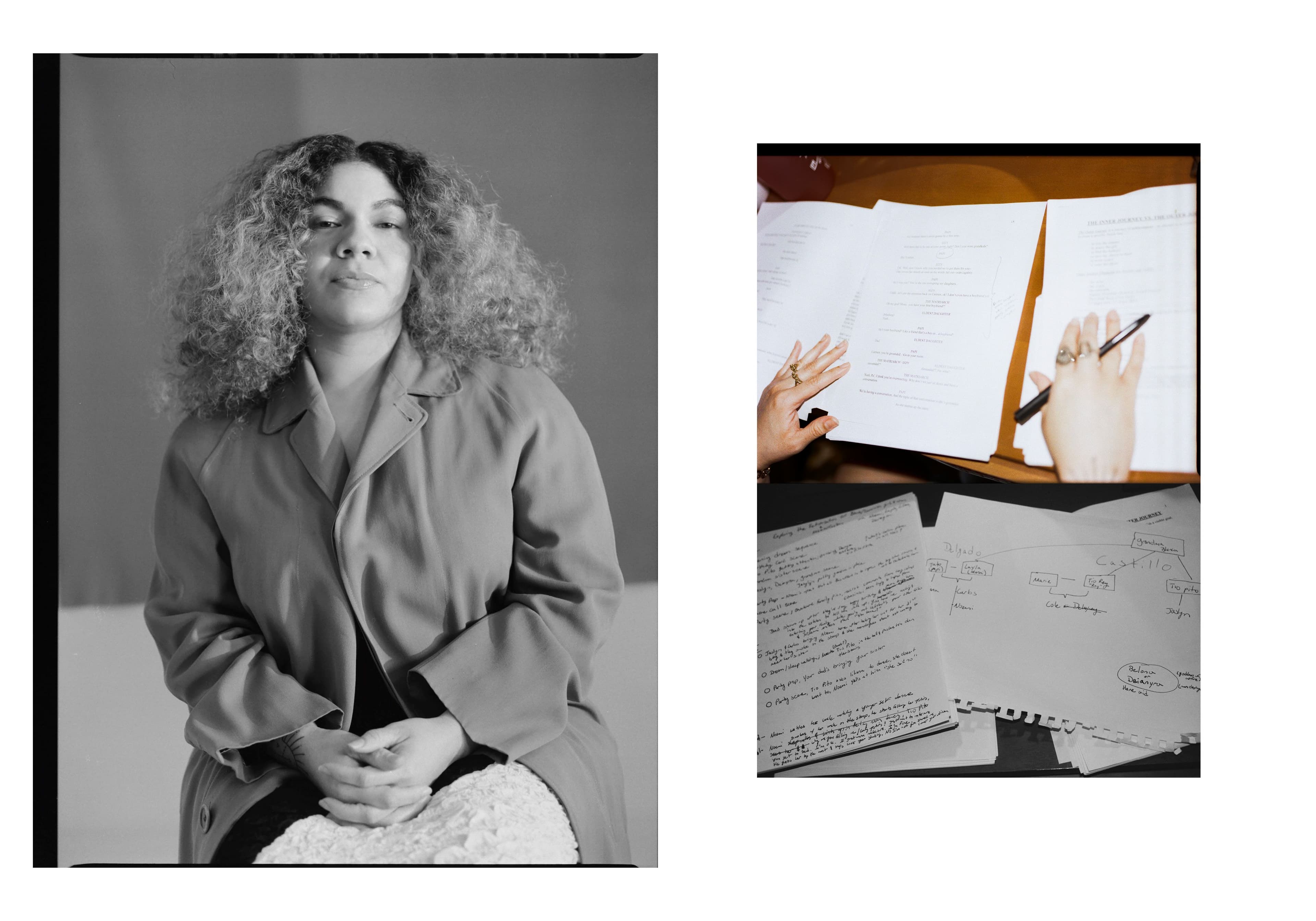

Artist: Daniella De Jesús

Mediums: drama, poetry

Place of Origin: pre-gentrified Bushwick

Dress by Mara Hoffman. Boots, De Jesús’s own.

On a scorching day in May 2015 at Yankee Stadium, as she was graduating from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, Daniella De Jesús received a call that changed her life. In the middle of Robert De Niro’s commencement speech, her agent informed her that she had booked Love Beats Rhymes, a poetry film in which the writer and actor was cast in a supporting role. Since then, De Jesús has dabbled in television and on stage but finds that her most honest performances happen when she looks inward.

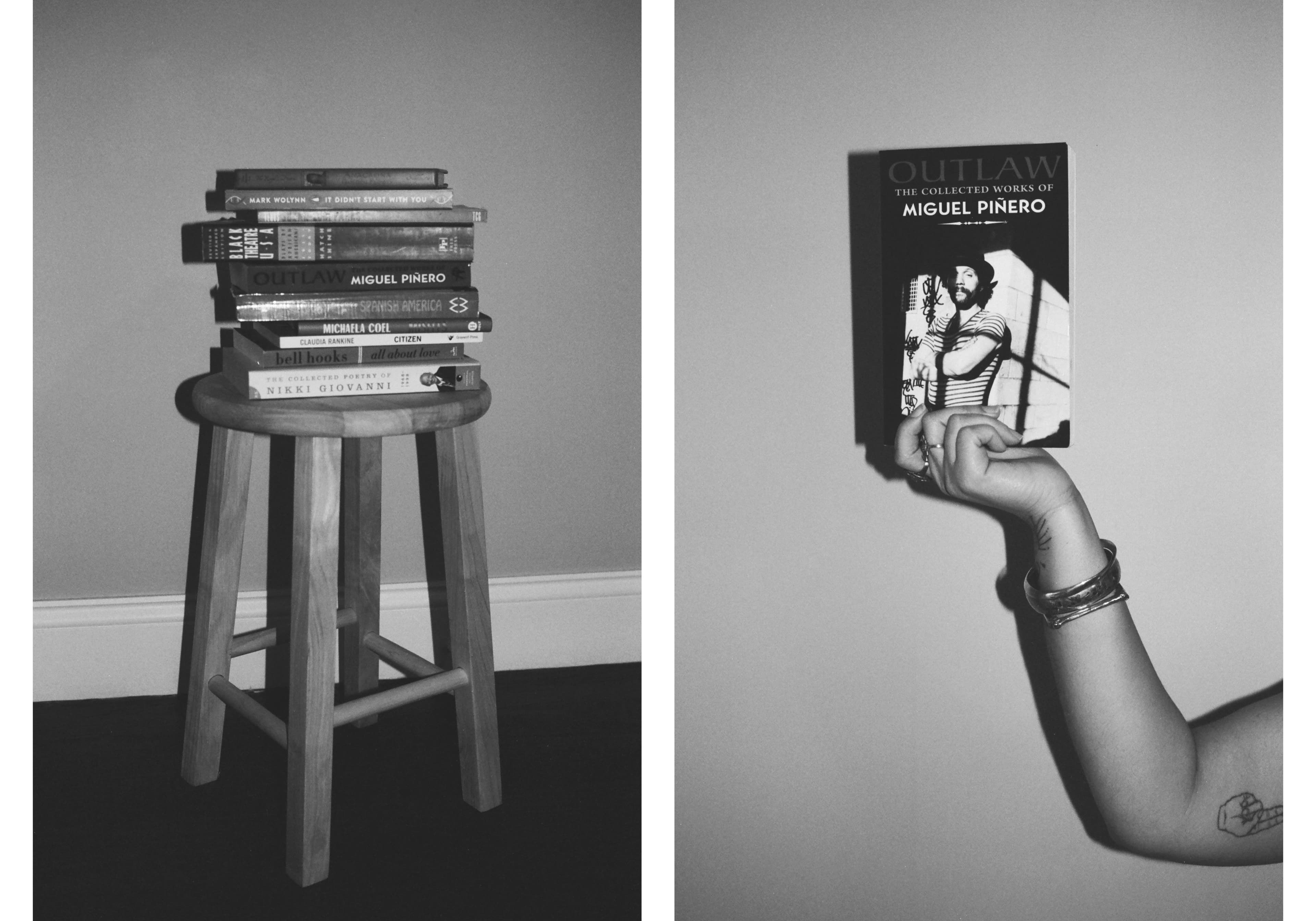

While De Jesús might not identify as a poet today, her writing, both personal and collaborative, has an intimate and introspective quality. Her first play, a one act called The Thief Cometh, deals heavily with the gentrification of her native Bushwick, Brooklyn. Her more recent works directly address issues of generational trauma and the lingering effects of colonization in Dominican-American identities. In working with these themes, she says she takes “from my personal life. I feel like that connection has always been there.“ Deeply influenced by the television shows she watched growing up as well, she has established a self-admittedly “weird“ style, one so deeply focused on trying to explain the unexplainable that she might leave her audience with more questions than answers. One of her most recent plays, for instance, Untitled Puppet Show, is about a child who becomes trapped as a puppet in their favorite television show, using surreal devices to explore perceived value and afterlives. “Life feels very surrealist to me,“ De Jesús reflects. “I have a lot of moments in my life where there feels like there was some kind of spiritual intervention.”

All jewelry, De Jesús’s own

The dreams De Jesús once had of becoming a Hollywood star dissolved as she spent more time with herself over the pandemic. She remembers the influence portraying the inmate Zirconia on Orange Is the New Black, a role she landed shortly after graduating, had on her. “I definitely took that for granted and I became swept up in the Hollywood madness,“ she recalls. “I really wanted to be a Hollywood actor because I thought that’s what being successful was.“ She notes a kind of shift in her priorities: “I’m much more interested in creating work that’s personal and meaningful and impactful. I just feel so much more responsibility as a storyteller now than I did before the pandemic.“

Along with this shift, she challenged herself in 2020 to pursue her long-standing interest in comedy. De Jesús began by writing, directing, and producing (with the help of the Stephanie Salgado) her series Talk to Me, which premiered on Instagram and which came about after experiencing the trials and tribulations of pandemic dating. She remembers brainstorming a project that didn’t require those involved to be in the same room, and came up with a mock dating show mimicking FaceTime calls. “It was like this little pressure cooker of a web series,“ she reflects. In addition to writing and directing, “I edited all the episodes, which I’d never done,“ she adds. “I don’t know how to edit, and nobody else did. So I was like, ’Okay, well, I’m figuring this out I guess.’“ Her comedic pursuits didn’t stop there. Earlier this year, De Jesús wrote a fifteen-minute standup set for the Dominican Artists Collective, a style of performance she never really focused on before. “Once I was up there, I loved it,“ she recalls. “I was like, ’Man, I could be here for two hours. I feel great.’ It felt really natural.“ For De Jesús, it’s obvious writing has a much deeper function than just connecting with an audience.

Left: Vintage coat by Burberry. Dress by Mara Hoffman. Right: All rings, De Jesús’s own.

Throughout her career, De Jesús has been refreshingly honest in sharing her experiences with social anxiety. For fear of pushing the trope of the troubled artist, or perhaps because it’s complicated to discuss, we don’t hear many stories of people in positions like De Jesús’s, how their mental health feeds into their work, and how it might also function as a way out. “I’ve reached a certain place in my life where my social anxiety isn’t as much of an issue anymore,“ she says. “I’d just accepted it as part of who I am and I’ve kind of learned to flow with it. But writing has helped me navigate a lot of my depression.“ She has now found the tools to manage her depression and anxiety, and both her early poetry and many of her later plays are powerful examples of the value of pouring yourself into your work. It might be difficult at times to put your own conflicts away and write, but once you do, as with any craft, those things fall away. De Jesús puts it simply: “Writing has always been a way for me to process what I’m thinking and feeling.“

From left, De Jesús wears dress by Mara Hoffman. Boots, talent’s own. Pombo wears dress by Fragmentario.

Artist: María-Elena Pombo

Mediums: textiles, fashion, avocados, water quality testing

Place of Origin: Venezuela

When María-Elena Pombo left Venezuela for France thirteen years ago, she knew she wouldn’t be back. For the visual artist now known for her work under the practice she calls Fragmentario, it’s the distance that allows her to apply her heritage to her work. “I had to leave to be curious and have distance to research it. These years in Venezuela have been very complicated,“ she reflects. “It’s a duality. There’s these two sides that can’t meet in the middle and it feels very extreme.“ But from her warehouse studio nestled in Brooklyn, Pombo beams about the potential of circular economies, conceptual fashion, avocados, and sending water through the mail.

Fragmentario, a personal brand Pombo conceived while she was still climbing the ranks of the fashion industry as a designer and practicing her visual art under the moniker to maintain anonymity, is realized in three chapters: Ahvacatl (the past), Rosa Terráqueo (the present), and La Rentrada (the future). Her work, in all of its depth, has meaning at every layer. The name Fragmentario was derived from a Google Translation of the word ’coalition’ into Galician, a language local to the northwest of Spain that her grandparents spoke. The practice seems to keep her most personal identity and her art separate. “I have this layer of protection. I’m a bit separated,“ she says. “In Spanish to be very vulnerable is a little bit more difficult, I feel very naked. With Galician, it’s this middle point that’s familiar, but I don’t speak it.“

Dress by Fragmentario

Pombo imagines a post-diasporic world, reconnecting with her roots by applying value and use to an everyday material like avocado seeds. Growing up, Pombo remembers “an avocado tree in [her family’s] house in Venezuela“ and the feelings about food and materials that are now complicated by distance. “When I go to the store to buy avocados,“ she admits, “it’s always a very strange feeling. My family doesn’t have this house anymore. My parents left Venezuela before me and there’s this huge Venezuelan diaspora in the world. Actually, when I see an avocado, it’s cute, because I think of family, but then it’s really sad, because I think, ’Well, we could be having fun gatherings but everyone’s left.’ So it’s always a very strange feeling.“

That sense of separation, combined with an interest in how different cultures limit their use of certain plants and animals, sparked an interest in Pombo to see what might become of avocado seeds depending on where they were grown and the mineral content of the water used to nourish them. She recognized that before it became a symbol of hipster/keto/toast hype, the avocado was just a fruit. “I didn’t know, of course, the avocado seeds could be used,“ she recalls. “I researched more about avocados and learned how they got to Venezuela. I experimented with the plant,“ which would become the Ahvacatl part of her practice. “I designed a capsule collection of clothes and made all the patterns and some of the samples with a factory that I had worked with [in New York],“ and dyed the designs with avocado seeds. In 2017, she organized an Avocado Tour in Europe, hosting workshops in different cities for two months over the summer before the final stop at Paris Fashion Week, where she presented her complete capsule.

Left: Poncho by Jil Sander. Right: Dress by Fragmentario.

That is the past and the present. The future, La Rentrada, interrogates a dilemma that’s left Venezuela, and much of the world, in a chokehold: how we have come to rely so heavily on petroleum and why we neglected to place more controls on its use in the past. Pombo’s grand ideas like these attract an audience more diverse than that of traditional, non-experimental art forms. Her practice, she says, “creates a very interesting system that allows me to talk to people that I wouldn’t otherwise.“ Her work is a speculation, and in that, must be resourceful. “I have met so many workers from kitchens in New York City and really developed this relationship with them. I wonder if I just made paintings or sculptures with traditional materials if they would be as invested.“ Luckily, we’ll never know.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.

Left: Dress by Fragmentario. Right: Dress by Fragmentario.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.