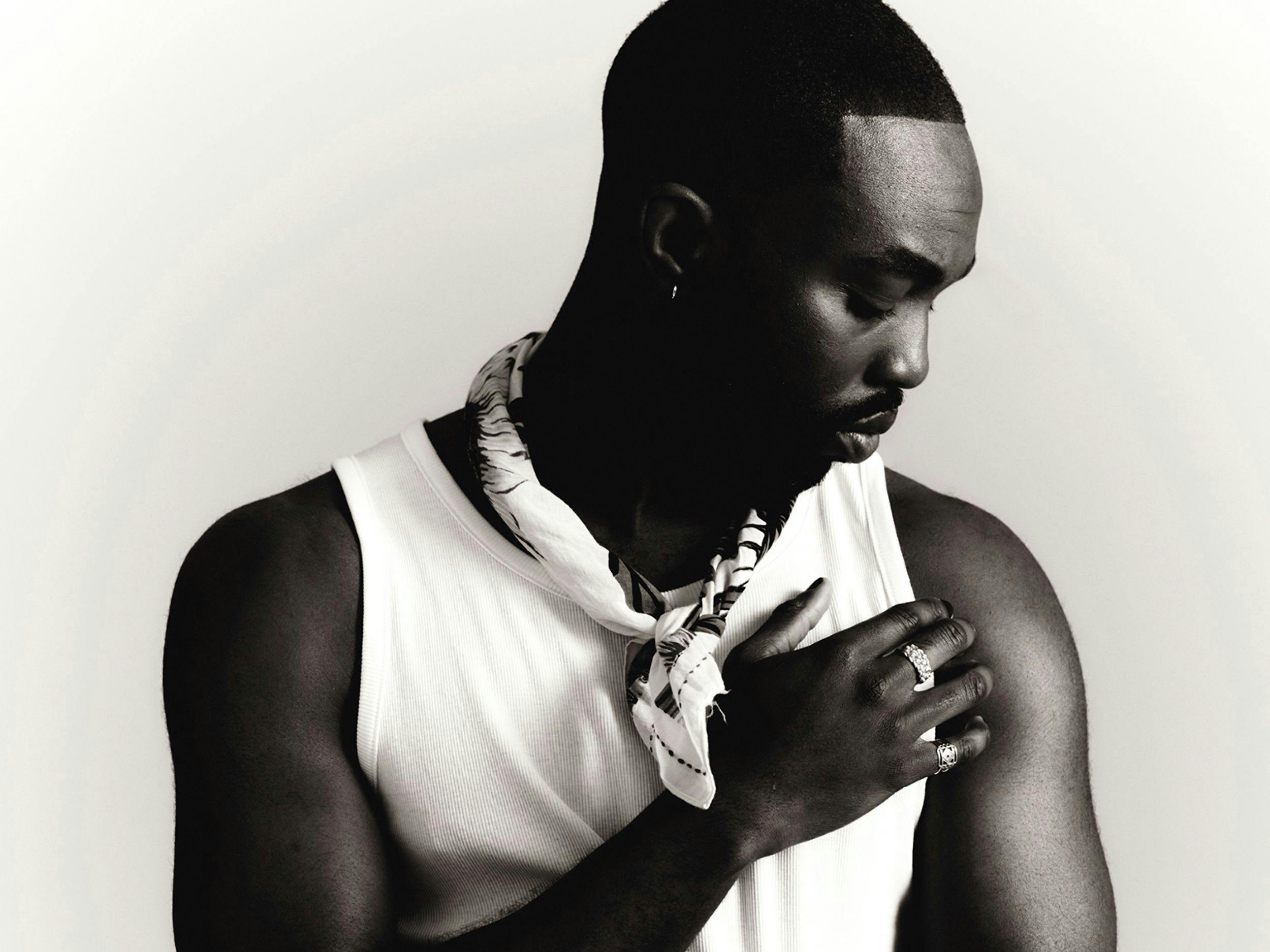

Jumpsuit by Alexander McQueen. Earrings, necklace, and rings by Spinelli Kilcollin. Necklace by Martine Ali.

Gus Dapperton Makes Music to Survive

Over the course of three albums, the 26-year-old musician Gus Dapperton has proven that he is willing to put in the work. On his latest, Henge, which he released this summer and has described as a love letter to New York, he tackles intense emotions while leveling up his vocals and production, a major step in a new direction after years of more intimate work. As he prepares to embark on the final leg of his latest international tour, starting with a hometown performance tonight, he speaks with his friend and creative collaborator, the author and Cero Magazine poetry editor Ocean Vuong, about growing up at the skatepark, the effort it takes to create, and why art needs to be desperate.

Suit by Alexander McQueen. Earrings and necklace (worn on back) Spinelli Kilcollin. Necklace (worn on back) by Martine Ali.

Ocean Vuong You’re a relatively young artist and you have such a wealth of a body of work—incredibly prolific. You’ve signed with Warner Records and it’s so exciting because you’re probably reaching new folks. For folks who are new to your music, the production is much more robust, but you’ve been making music for a long time out of your bedroom. I would love to hear how you got started and particularly why you decided to keep it indie for so long. I think that’s what’s really special about your work. Some artists, they make an indie debut and then the sophomore album, they hop onto something big and sometimes you feel like you lose them before you know who they truly are.

Gus Dapperton First, I got into music when I was in eighth grade. I tried to pick up the guitar one time. It was frustrating to learn and I didn’t feel like any musicianship really came naturally to me but I was a huge music fan always and always loved discovering new music. My friends and I first started getting into it by freestyling at the skate park. I was really into old-school hip hop beats. In eighth grade, we were introduced to GarageBand in a music class. I was already pretty good at using the computer and I would always edit skate videos and things, so I felt like the interface wasn’t that foreign to me. When I hopped on there, I was like, “Oh my god, this is how people make beats,“ which is what I was obsessed with. Oftentimes, I listened to music that had no vocals on it. I just became obsessed with it after that and I made a song. There was a “songwriting contest“ and I won it and then I was able to go on the town radio station. I was like, “Oh, I love doing this and I can already tell this is going to become a passion of mine.“ I just made beats for a while. My friends were all rappers and vocalists and they would all rap on my beats. Then they all started fading out of music a little bit and I was like, “I have a lot of things I want to say, so I’m just going to try to sing.“ I was uploading music to SoundCloud constantly and I think when my music started to get a little bit of traction, I almost felt like I just wasn’t ready to have it be my job. It was all passion and learning to me and discovery. One of the reasons why I was indie for so long was because I didn’t want to make it a duty of mine. I still wanted it to be a passion and a hobby that I’m just obsessed with and that I loved. I still wanted it to just be my form of expression, how I wanted to do it. Because I grew up in Warwick, New York, in this little town, I didn’t have any mentors or peers who were affiliated with music or the music industry. I was just a little bit naïve to what actually went on in the music industry. I think for safety reasons, I always thought, “I don’t want my vision to be compromised by anything.“ I realize now it’s not really like that but I think that’s part of the reason why I was indie for so long.

Shorts and boots by Ferragamo. Earrings by Spinelli Kilcollin.

OV It’s so varied. There’s the horror stories we hear and then when you go in to work with partners and colleagues, you realize that depending on the room that you’re in, you have a voice. When you go into a larger production, it just means there’s more tools. It doesn’t mean the horror stories don’t exist. I had a very similar experience as a poet. It may be a reach here but as poets, I feel it’s very much like we’re always DIY. The first thing they tell you as a poet is there’s no money in it. I had an agent reach out to me—who’s my agent now—who said, “You should think about writing prose and we can sell your book to a bigger house, a bigger publisher.“ I was very nervous and I said no. That’s the prerequisite of one’s writing career and I said no to my agent because I got freaked out. I said, “Oh my goodness, does this mean I have to hand in homework every week?“ I was scared and she said, “Just come to the office and let me explain it to you.“ I had the same thing. I worked on my own book for eight years, just alone. What I see in your work, preserving that indie spirit, is this allegiance to wonder and play. I’m going into deep literary theory here but one of my heroes, Sergei Eisenstein—he’s a Soviet-era filmmaker from the twenties—said, “It’s not about avoiding cliché in art, but it’s about introducing estrangement.“ You can have a cliché that’s so sentimental, so overwrought, but if you make it strange, if you put it elsewhere, all of a sudden it’s no longer cliché. I see that in your work. There’s this playful, childlike familiarity. The bowl cut, that’s how I was introduced to you. As an Asian-American, I have an affinity, allegiance to the bowl cut. “Who’s this white boy rocking a bowl cut dancing in the middle of the street?“ I learned that you cut your own hair. We’re in a culture starved for authenticity. You can’t buy it, you can only find it. You can’t fabricate authenticity. What was so refreshing about your work is a sense of tenderness and a sense of play. It comes out of skate culture. I think there was a whole generation that came out of the early aughts that was influenced by the skate video. I was one of those kids too. The skate montage—talk a little more about that influence and how music functions as a background to rhythm in the movement of the body. Skateboarding is a kind of performance, it’s a dance.

GD I do relate a lot of things back to that, especially where I grew up. It was more of an athletic, sporty town. By default, because I was a skater—and we had a really small group of kids—we were naturally more “outcasts.“ Because of that, it inspired us to be more individual as opposed to more in a conformed environment. With skateboarding, style is literally kind of everything. Every art form ties into why you gravitate toward a favorite skater or something. It’s about the music they chose and it’s about the person they chose to film and it’s about the style of how they skate and it’s about the tricks they chose to do and it’s about how they dress. A lot of my fashion sense came from those skaters that I was drawn to. I feel like you can naturally see them being individuals. To me, it was kind of an art form in that way. Skaters are all doing different things. I found all my favorite music through skate videos, especially indie music. I really got into it from that.

OV You said something so interesting there, that what we often glaze over is skate culture is highly interested in æsthetics. It’s an individual sport—it’s not a team sport, but it’s a community sport. You get together and you scope out the stairwell and you’re all there and you’re cheering this person throwing their body twenty, thirty times into the ground. If that is not counterculture, I don’t know what is—a group of kids cheering someone breaking their arm. You see skatewear and streetwear, you see Supreme coming out of this ethos, but you don’t really see jock culture being influential beyond its milieu. Skate culture is so indelible in that way. You mentioned singing and I might be wrong here but I’ve noticed that your voice has become so dynamic from the first live performances to now. The range has opened up. My friend in the band Pinegrove, Evan Stephens Hall, said something really, really beautiful one day: “Anybody can sing. The voice is already a perfect instrument, you just have to widen it.“ It’s the only instrument that can be widened. It goes back to this idea of this medieval Christian ethos that the only worthy instrument was the voice. The chorus and the church choir were the only voices that were allowed in medieval churches. Did you train your voice? How did we get to the voice of Gus Dapperton in Henge?

Shorts and boots by Ferragamo. Earrings by Spinelli Kilcollin.

GD I completely agree with that sentiment that anyone can sing. A lot of my favorite artists are artists who don’t necessarily use the tools that we would consider classically trained or technically really sound. Oftentimes, it’s just about the tone of voice that I really gravitate towards and the timbre of someone’s voice and the uniqueness of their voice. I didn’t even sing along to songs in the car or in the shower. I never really tried it until maybe I was seventeen. I was a really late bloomer to it and I was really timid at first. I had a really small use out of my voice and as time would go on and I’ve been performing and touring, it’s just grown a lot. I’ve also taken some lessons to try to figure out how to expand it. A lot of times, like in my early projects, it’s my expression and my passion. To me, it still all felt like an experiment and a learning curve, just releasing them and making them and trying to make a holistic thing, and all of them are experiments. It took me a really long time and I think for years I’m still going to be figuring out other ways I can use my voice. Because the inception of it was at seventeen, it’s only been not even ten years of me singing so I still have a lot to learn. I was so excited when I started figuring out these other pockets of how I can use it differently. I do think anyone can sing for sure and it’s just about how you how you use it. I think people really appreciate when you’re vulnerable and expressing yourself.

OV One of my favorite poets, Federico García Lorca, had this incredible theory about art. He would observe flamenco dancers and singers—he described it as harvesting blood from the ground, they would stomp the ground. He developed this idea called ’duende.’ He said that duende in art cannot be developed. It can be discovered, it can be made room for. You can have perfect pitch and all that, that’s training. But duende, he said, comes from a deeper archaic understanding of the suffering of the world. That’s kind of a catch-all for what we call ’soul,’ or ’the spirit’ in the church. I felt that in your work, the vulnerability that comes through. I think that was what really drew me to your work, that there’s this raw undertone in your vocals that comes through and that’s why we call it ’duende.’ It was already there and you just found the instrument to articulate it. You’re still finding those instruments because I still see the through line from the first album to the latest is that there’s so much emotion. It made me think about lyrics. The trajectory through the albums went from the surreal, playful lyrics to something really grounded, tender, vulnerable, and really open to these emotional truths—like the ideas of mental health, depression, survival, addiction in “Medicine.“ It really started to come through this tangible common ground where you started with this playful, surrealist, almost witty movement and then you grew into a place where a lot of people, I think, in your recent album, started to say, “Oh, wow, this is not just a spectacle—the kid in the bowl cut in a neon vest. There’s a personhood behind this.“ And of course, there was! But the way you’re plotting your albums, it arrives at this vast emotional space. I think that’s why the fan base has been much more myriad and intergenerational, it’s really opening up. Can you talk a little bit about the trajectory of your songwriting?

GD Oftentimes, my early songs, I would just write a poem and then turn it into a melody. With each new project, I had a different creative process. At first, a lot of it was just a beat or a poem and then I would try to combine the two because I was really still figuring everything out. It has taken a while for me to be vulnerable, super vulnerable. A lot of my early stuff, I really am still proud of a lot of the lyricism but I think sometimes I would subconsciously mask exactly what I was trying to say because I was scared of people. With each different album, there’s a little bit more of a goal behind it. With my early stuff, I was just trying to make songs that I would listen to myself and make cool sounds and write really cool rhythms and melodies and lyrics. Then with my album Orca, the goal was really just for me to have a cathartic experience because I really, really needed it at the time. I just needed to use it as therapy and expression. I don’t always have an intent with writing every song for it to come out but with Orca, especially, I wrote a lot of songs where I was like, “I don’t know if I’ll put these out because they’re really personal and a bit more forward with what I’m actually saying and what’s actually going on.“ But I realized when I showed them to people that some of the songs became important to them and they appreciated that I was being vulnerable. Now, I do want everyone to understand what I’m saying or be able to connect to the lyrics a little more easily but I also really like metaphor and creating these big ideas out of a small sentiment. I think that’s something with your writing I really love. It’s the perfect mix between poetry and things that people can still relate to and understand at first glance. That’s something I strive for with my lyrics nowadays.

All clothing and belt by Dries Van Noten. All jewelry by Spinelli Kilcollin.

OV Oh, that’s so touching. I think when people realize that there is an artist engaging with the world—so many artists, particularly artists that come out of indie circles, they could be spectacles or they’re very aware of the spectacle of the video: “How do I make a catchy video?“ Then they usually fade away because when people say, “Oh, there’s a flashy thing!“ everyone gathers around and they say, “Okay, well what else is there?“ When there’s nothing there, the crowd starts to disperse. We’re often told that in the culture, whether we’re making any artistic production, you need something eye-catching. We want all the eyeballs or readers. But in fact, I think that’s actually easy to do. It’s easy to create fireworks, you just set it up and people come. The hard thing is, what will you say when the crowd is there? What will you say when the auditorium is packed and everyone’s listening? I think a lot of artists choke on that point. We don’t talk about that. How does one work through having something to say, and something that’s shareable and substantial, that underneath the strangeness and the beauty is something that’s actually very, very archaic and human? I think you’ve really developed that. Many people might not realize how hard you work. When I visited your studio in Brooklyn, I was really surprised when I saw your space because it was so curated around the work. There’s a keyboard, there’s a studio, and then there’s a piano in another room. Sometimes with the younger generation of artists, people think everything’s in a bedroom, everything’s like, “Oh, it’s just a side hustle.“ There’s a kind of very cool ӕsthetic to that, “Oh, this just flows through me.“ But actually, I think it’s important to reiterate—at least from my gaze—that what we’re seeing, the beauty, the dynamism that we hear, comes from hard, hard work. Watching you work in the studio and on the piano was so revelatory but it was not surprising to me. I said, “Oh yeah, of course. The magic that I hear doesn’t come from just anywhere.“ We love that. Particularly in America, we love this idea of the prodigy, that the wunderkind just closes their eyes and then beautiful work comes out of their fingers. But you have a labor practice of dedication there. Can you talk a little bit about your work ethic?

GD One of my mantras I try to get across to people is—I think people oftentimes think I’m shooting myself down when I say I’m not a good singer or I’m not a natural. I’m saying I’m not a natural because I’m not. I’ve put in tons of time and effort and work into understanding all of the tools so I can get across things I think are important to say and sounds that are important to make. I think there are people who are naturals at instruments and vocals and lyrics and melodies. I really just practiced all of those tools so much and I care about it all so much that I think it’s important to note that it isn’t a natural progression. It’s a lot of practice and work that goes into it. I think I write pretty much a song or I write a poem or I write a melody, one a day. I write one a day. Going back to what you said about duende, that’s something that I subconsciously relate to and I always say pretty much five percent of the music I make sees the light of day and five percent of the music I make I think is important to share with the world. Because only five percent of it is desperate and that’s how I talk about musicians that I like. I describe songs as being desperate and not desperate. Oftentimes, I just listen to songs that are desperate. What I mean by that is it feels like they needed to make this song to survive or to move on. It can still be an uplifting song, it can be just a beat, it can be house music that doesn’t have any vocals on it, it can be noise music, but oftentimes I feel if you react to a song that way, you can tell it’s desperate because you’re drawn to things that need to be in the world. That’s how I feel. I always know when a song is meant to be alive. Oftentimes, I’d write something that was not coming from a greater source in me but I think all the songs I’m really drawn to are the ones that are from a greater source of reach and knowing how I’m feeling and trying to get that across as best I can.

All clothing by Saint Laurent. All jewelry by Spinelli Kilcollin.

OV We hear it. I hear it in the urgency. When people say, “How do you get your work done, with the world and with being a person in the world?“ which I think in every generation, every epoch, is a position of horror. When people say, “How do you get your work done?“ I say, “Well, I get my work done because my urgency to speak outpaces my terror.“

GD A hundred percent.

OV That’s it. There’s no like, “Calm, I will now produce poetry.“ There’s some days where I can beat it and there’s some days where I’m just shut down to silence because it’s too much. I hate to say that it’s kind of a battle. Sometimes it feels like you get the work done when you steal it—you steal it from yourself. It’s like an inner thievery, where the world conspires to silence you, to shut you down. The industry, right? It’s very hard to make a living as a musician, very hard to make a living as a writer. This idea of a desperate song, I think that is the marker of sustainability in an artist because at the core of all the things—the chord progression, the styles, the stylistic changes in your wardrobe, your look—all those things are the debris of the comment. The core of the comment is that desperation, that’s the engine. I want to talk a bit about gender-bending and your æsthetic, which is nonconformist to these heteronormative ideas of what a singer or musician should be. Of course, in music we can go all the way back to Little Richard putting makeup on, Michael Jackson, David Bowie, but every generation has a different context. In the eighties, it was very open, very feminine and glamorous. It was not uncommon for masculine rock musicians to be bedecked with jewels on their sequins and clothes. But here we have a different vibe. I’m curious what brought you to this kind of open, gender-fluid expression. Also in your music, in certain songs, it’s hard to know—it doesn’t matter but it’s hard to pinpoint the gender of the speaker.

GD I have a lot of mantras on all of this. What it all ties down to is what you consider authenticity. I think people are afraid of using that word because it’s hard to describe what it is. By definition, it’s being the most authentic self and expressing yourself in the most authentic way. To me, what that means is letting everything you’ve ever been inspired by seep into you and your life. Oftentimes, there are artists who don’t let all of their inspirations show in their work. For me and for people in our generation, we listen to every genre of music and it would be inauthentic to me to not let hip hop or country or pop or all of these things seep into one piece of art. I think fashion is the only form of art that is separated oftentimes by male and female. That’s something that always bothered me because I think body types are so dynamic and different. It feels weird to completely separate it. I just feel more confident expressing myself in women’s clothes. I think it just should generally be not as binary. It’d be the same with music. You don’t say, “I want to listen to a female singer or male singer,“ you just focus on the music. That’s my motto with all that. You’re inspired by so many different walks of life, you just have to let it seep into you and let it seep out.

All clothing and shoes by Saint Laurent. All jewelry by Spinelli Kilcollin.

OV That’s so gorgeous. What you’re describing reminds me of this Buddhist koan of five blind travelers who are asked to come and touch an elephant and describe what they are feeling. One touches the trunk and says it’s some kind of hose. One touches the leg and thinks it’s a tree. One touches the stomach and says there’s a great warm, sunbaked wall. The idea is that there is just phenomena interacting with the world but their understanding or knowledge is conditional, selective, and myopic. You’re approaching the world in that way. It’s like, “What is this? Let me just hold it,“ rather than, “What is this? Where do I put it?“ I think what you said was really beautiful about when we listen to music. Maybe that’s actually the best way to describe the most fruitful encounter with the world. It’s not, “Is it a male singer? A female singer?“ but “There’s music occurring.“ I think the beauty is that our ears are the only things we cannot control. We can shut our eyes, close our mouths, but the ear, through evolution, has always been open. It’s the only sense that’s always on, if we can hear. I think there’s something to that. Maybe there’s an ancient knowledge there, that if we lead into the unknown with our ears, rather than our eyes or historic judgment, then we actually can see something as it is. That’s the Buddhist idea of “don’t see something as it’s told but as it is.“ I love how you’re approaching that. Going back to skating, did being a skater and being in that outcasts’ milieu make it more permissible for you to gender-bend? Were there any homoerotic foundations in those circles? I remember that I was very jarred but it was the skaters who were the ones that embraced my queerness. In high school, they were just like, “Oh, cool.“

GD I experienced the same thing, just because I had a small community of kids who were all from different walks of life and we all just became brothers and whatnot. We felt like we became a family and still a lot of my bandmates are kids I grew up with. All of them were always very accepting. But I do think in skate culture in general, that’s one thing that has had to get a lot better over the years, was just open-mindedness because it is a very male-dominated sport. I think it’s gotten loads better in the last decade but in my time at least. Our crew was definitely more accepting and open-minded just because we were expressing ourselves to the fullest.

OV [When you perform,] it truly feels like the social system of the skatepark onstage, there’s just total collaboration and rooting for each other and it makes a lot of sense that transition. You can feel it and I think what I really see when y’all perform is a joy. Some bands, it’s just really great pieces but this doesn’t look like pieces when I observe it. I feel like it’s always been there, like it just coalesced like a fungus coalesces together, like it’s just all there like a mushroom. I think that’s really exciting. I think it’s really uplifting for a viewer to see that everyone just really loves to be there. Maybe I’m projecting onto it, I’m sure there’s difficulties in touring and life but you can just sense that there’s something beyond a job, which goes back to what you said before. It doesn’t look like anyone has to do this to get notoriety or money. The primary function and goal seems to be the joy of making music and it’s really infectious. You can see it in how you foster that ethos.

GD We definitely have a ton of fun playing, we’re always smiling and stoked on each other. I’ve been telling my bandmates some things to think about before going into the night and oftentimes, what I’m trying to get across is the goal of performing. Once I started defining this vocabulary in my head of what the goal is each night of playing, it has really helped me perform better and relax and give good performances and experience joy too. Our whole thing is basically, it’s not about us, it’s not about hitting the notes perfect—it’s about inspiring the people who came to the show, inspiring the next generation of artists, of heroes, or whoever is at our show, and making them feel seen like we had once felt seen by someone. Oftentimes, we’ll go to these small towns in the middle of the country, like Arkansas or something. It’s like, “Why are we playing here?“ but the whole thing is the people that are coming to show are coming because they didn’t think one of their favorite artists was going to come to their town. They’re really excited about it and they’re the ones who maybe don’t fit in and want to feel seen by someone and listen to music that is more open-minded and individual. That’s why I have so much fun. It’s just about giving your whole hundred percent. If I felt like I did that, then I think the fans can also feel that.

Vintage shirt by Helmut Lang. Top by The Row. Pants by Willy Chavarria. Underwear by CDLP. Earrings, necklaces, and ring by Spinelli Kilcollin. Necklaces by Martine Ali.

OV Wow, you’re right in that people don’t get to decide where they’re born but they have their own journeys. When I was looking at publishers for the novel, one editor who I didn’t end up working with said to me—I thought it was very strange but they said, “What will the Midwestern reader think about this book?“ I think what they were talking about was the sexuality, the queerness, or the unconventional form. I thought, “The Midwestern reader—I don’t know, there are people who have sex, maybe, God willing, queer sex in the Midwest.“ It was just so interesting that, depending on where we are, we don’t imagine that people have fully fledged lives in certain parts of the world. Sometimes it does require coming out and seeing it for yourself. It’s like, “Oh yeah, there’s me in this crowd.“ There’s someone like me because they don’t have the means to just up and go to New York or LA or San Francisco. They have to make their life and their joy where they are. I think that’s actually really important for my novel. The trajectory, usually, of a Bildungsroman is that you get out of this shitty old town and you go to the big city. That’s a very traditional trajectory. It’s frustration and then college is just suddenly great, you’re done. Once you go to the big city, it’s the panacea, especially for queer folks. It’s like, find yourself in the Big Apple. I wanted to have a book that did not allow that for any of the characters. It’s like, no, whatever you’re going to deal with, good or bad, paradise has to be made by making it. You cannot escape it geographically. I wanted that constriction for myself. When I took away the big cities, I had to ask the characters, “Well, how do you make this livable? How do you make joy here in the river beside a tobacco farm?“ I feel that a lot in your work. I feel that it’s coming from being in a more rural or more provincial situation. Many profiles rarely ask this of artists, but I’m genuinely curious, what do you want for your work? In the best-case scenario, what do you want it to be in the world? What’s your wish? Sometimes it never coincides, our work never turns out the way we want it, but in the best-case scenario, in the best world, what do you want for it?

GD I have had this change multiple times but I always have had one thought that has always stayed true. Oftentimes, you look at the numbers of things. Maybe you want more people to see it and there’s always a new goal of how many people that can affect. But at the end of the day, I make music, honestly, because I need to in order to survive. The serotonin I get from discovering the song in the process is my favorite feeling in the world. It’s something that I don’t think I’ll find in anything else. I’ve been able to wrap my head around more of what I want and what I want it to be in the world. It really is truly just about who it affects and not about who it doesn’t affect. If one person listens to it, if no one listens to it and I just listened to it and the discovery of making the song was a fulfilling experience, to me, that’s all I can possibly ask for. Yes, it is nice to be able to pay my rent from doing something that I love unconditionally but at the end of the day, I just am trying to make the truest form of expression and trying to say how I feel in a sonic way. If I felt like I did that and the audience who is listening to it feels that, then I feel successful in my purpose for making music. It’s just about the people it affects and not who it doesn’t affect. Once it’s out there, it’s all for them.

Henge is out now. Dapperton performs tonight at Webster Hall, New York.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.

All clothing and shoes by Balenciaga. Earrings by Celeste Starre.

All clothing by Celine. Earrings by Spinelli Kilcollin and Celine.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.