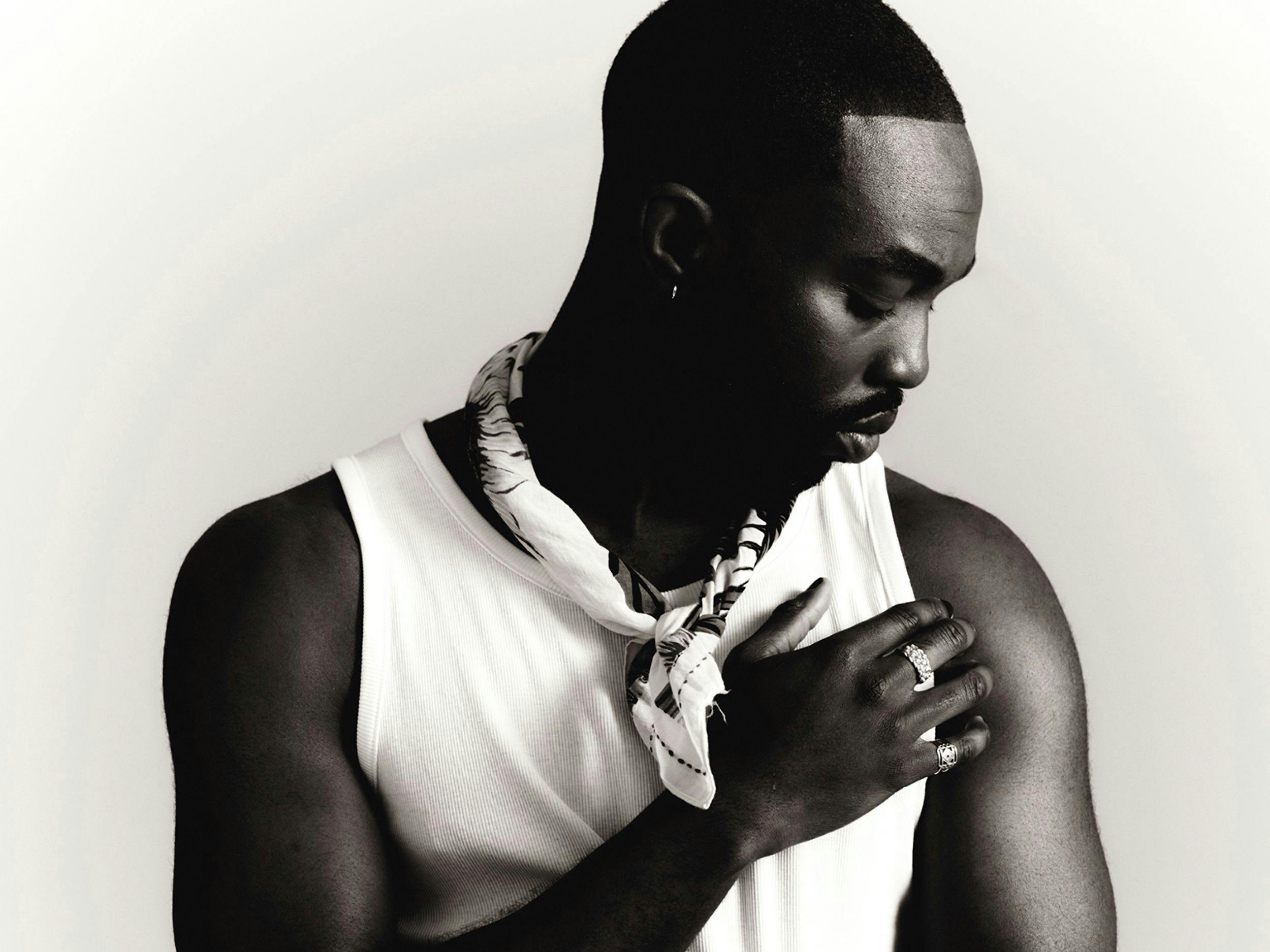

All clothing and boots by Gui Rosa

The New School

Much of London’s reputation as a capital of cutting-edge fashion can be traced back to Central Saint Martins, which has educated dozens of celebrated designers, including Alexander McQueen, Riccardo Tisci, and Stella McCartney, for decades. Its most recent graduates, who have entered the industry at a time of immense upheaval from pandemic lockdowns, Brexit, political polarization, the climate crisis, and the legacy of racism, prove that the spirit of creativity and individuality is still strong on campus.

When I called Gui Rosa last fall, the young London-based designer had just wrapped his biannual party week. “I don’t do parties. I go to fashion parties and I go sometimes to a bar,“ he said over Zoom, cheekily adding, “That’s really a fashion party.“ The 26-year-old, born and raised in Portugal and part of CSM’s 2020 MA graduating class, had been out every night for London Fashion Week (he says he hibernates and emerges twice a year for five to six days of performance and mingling), followed by a trip to Milan to introduce his Gucci Vault capsule collection. “There’s a kind of expectation,“ he sighs. “I was doing three outfit changes per day—with two hundred crystals glued on my eyelids with eyelash glue. I do the whole thing, or I don’t do it.“

This ethos—all or nothing, with a sharp dose of humor mixed in—infuses everything Rosa does. His eponymous line of crocheted menswear, intricate and flamboyant, is influenced by both his glamorous grandmother and “what I experienced in London as an adult dressing in a certain way and receiving, I don’t want to say, ’harassment,’ but seeing myself through the eye of a random male,“ reflects Rosa. His garments—take the thigh-high lame knit cowboy boots currently available at the aforementioned Gucci Vault—are high glamour, queer subversion, and modern-day John Waters all in one. A gorgeous crocheted take on two-tone denim “jeans“ plays with hyper-masculine archetypes and feminine detailing. A denim mini-skirt finishes with flamenco-style, butter-yellow crochet frills. La Veneno is a hero; the American-French singer Arielle Dombasle is another.

“I always loved fashion,“ Rosa reflects. “I just wasn’t necessarily sure of how I was going to be a part of it. Within time, I realized that design was the best path for me, just because I love texture and fabrics. I think it’s quite instinctual. You just run to things, and you want to touch everything. It’s also the only thing that I’m really okay at, you know? I had no other options.“

Rosa’s use of material and deconstructive approach have a quick impact. He suggests the quieter elements of his design—a focus on slow fashion and care in craft-making—may be equally radical. “Some people in their twenties want to wear a tracksuit bottom and feel like they’re in the sofa while they’re walking down the street and then have an expensive handbag,“ he says, referencing the pervasive machine-made garments now sold as luxury. “But some people want to be dressed top to toe and feel like they’re dressed as a weapon.“ —Ashley Simpson

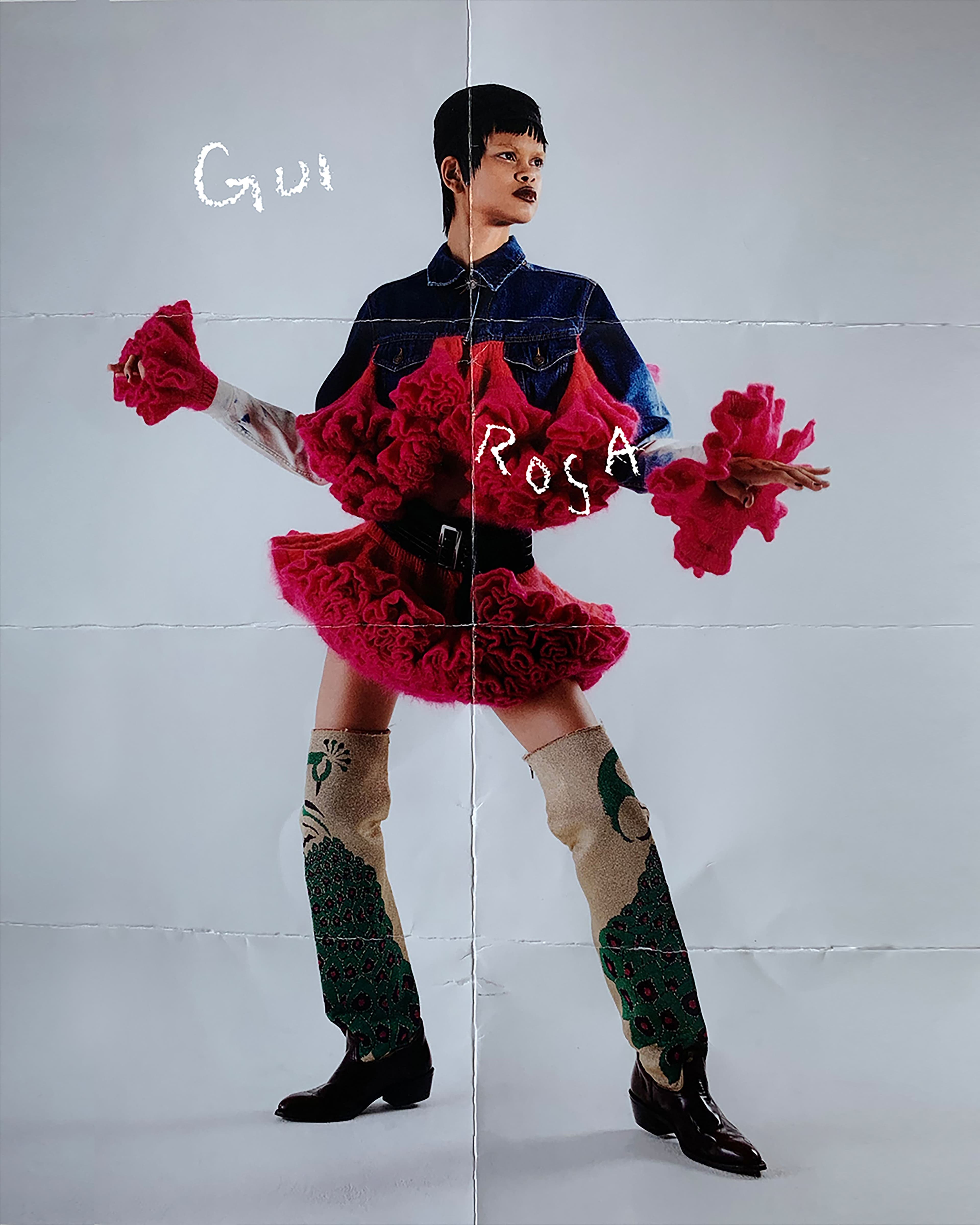

All clothing by René Scheibenbauer. Boots by Maryam Nassir Zadeh.

Anyone who has ever dismissed fashion as superficial or frivolous needs to look at René Scheibenbauer. The Austrian designer doesn’t just imbue clothes with meaning, he considers the meaning before he even gets to the drawing board (or, rather, his Lewisham home-cum-atelier in London). “I’ve managed to discover a really personal approach to fashion design,“ he says.

It all started during his final year at Central Saint Martins when, for his graduate collection, he “started to develop self-initiated research workshops surrounding aspects of art therapy and self-exploration.“ Instead of, say, turning to culture or creating a mood board every season, the thirty-year-old designer carries out mini social experiments. “I am interested in how people use clothing to express sexuality, emotion, and personality,“ he explains.

What does this entail exactly? Scheibenbauer gathers together people, other CSM alumni or his Instagram community, for workshops that explore how clothing makes them feel. They could be engaging with clothes tactilely while blindfolded, moving and dancing in them, or even “taking themselves on a date“ while wearing them, he says. After the workshop, he debriefs with his group using questionnaires and then gets to work. In more commercial circles this would be called market research, but for Scheibenbauer, it’s all part of what he calls “emotional dressing.“

Whatever its name, it informs all of Scheibenbauer’s designs and makes them stand out in an oversaturated market. As part of his CSM graduate collection in 2018, he designed The Empathy Jacket. With space for two people, it literally forces them to interact and guide each other while wearing it. Standout pieces like this are what helped Scheibenbauer win runner-up for the L’Oréal Professionel Young Talent Award and land global stockists such as APOC and Zen Source Clothing.

This interactive element remains a key component in his practice, encouraging movement, consideration, and play all at the same time. Unapologetic functionality mixes with pure æstheticism in fastening- and pocket-laden pieces, and particularly in the convertible looks: suits with packable hoods, trousers that unzip to create shorts, or blazers that can be slung cross-body when not worn (great for dancing, no doubt, in a post-lockdown UK).

Sustainability is also at the heart of the brand. “When starting out, it was relevant to every critical decision made about the launch,“ he explains. The designer keeps sourcing within Europe, with lots of production based in London to lower the label’s footprint. Materials are responsibly produced, with recycled fibers and deadstock prioritized.

Throw in the collaborative elements, with his peers during workshops or in production with other creatives (like print designer Anya Gorkova) and you’ve got the four key pillars of René Scheibenbauer sussed. Emotion, interactivity, responsibility, and community—what could be more meaningful than that? —Abigail Southan

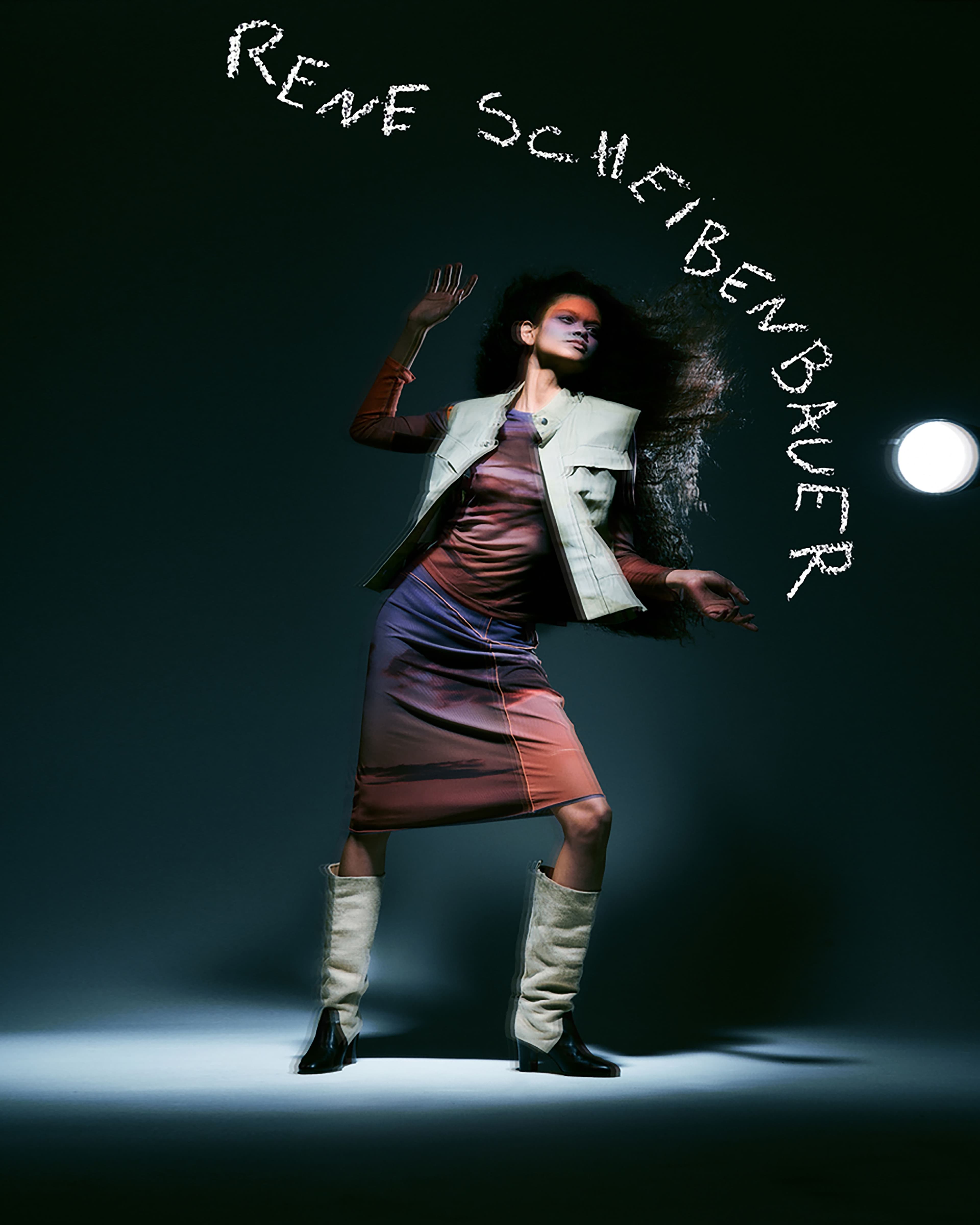

Jumpsuit by Masha Popova. Tights by Calzedonia. Boots by Maryam Nassir Zadeh.

“I don’t have a nice story to tell,“ says Ukrainian designer Masha Popova. She’s speaking of her fashion origins at Central Saint Martins, from which she graduated in 2020, showing slouchy repurposed nylon boots, denim envisioned with couture techniques, and “rusty“ butterfly embroidered bra tops—pieces already worn by a who’s who of the Instagram/TikTok era. Dua Lipa, Bella Hadid, Lil Miquela, Kylie Jenner, Billie Eilish—if you can name a Gen Z star, they have probably donned Masha Popova. “I wanted to be a hairdresser when I was a kid,“ Popova grins. “I was already cutting all the blankets because I was ’training’ to be a hairdresser. But I guess it was more like a designer, cutting fabric.“

Educated as an architect at a very young age—Popova graduated at just 19—the creative came to fashion with time. “It was always at the back of my mind,“ she says. “Then when I started studying architecture and working in the field, I realized it’s a bit of a depressing life. You work in front of a computer in the end. I wanted something more spontaneous.“

She eventually landed at Central Saint Martins, logging time interning at Celine and Margiela under John Galliano’s guidance before establishing her own line. Popova’s æsthetic brings together disparate experiences and references. Take the tracksuits converted into sculptural femme gladiator dresses from Fall 2021—minis, with a color palette one might imagine in another world’s natural environment. She melds materials (old denim, tracksuit nylon) and memories of Nineties and Naughties Eastern Europe with tricks of couture (the rose drape) and trans-historic discoveries (a hood early female bikers wore over their helmets, Nineties crime thrillers), her own experiences linking them in new conception. The shapes and the colors—vibrant, saturated, near psychedelic—are unrestrained and imagined. “Nonchalant elegance“ is how Popova describes it.

“I wanted to translate them through my understanding of fashion, my language, how I speak, because when I was growing up, haute couture was something I didn’t really know existed,“ reflects Popova. “The only fashion I knew was through going to second-hand clothes and looking at what people were wearing and obviously, I was a teenager. I was growing up through the Nineties in Ukraine. The Soviet Union had just collapsed. There were no magazines. None of that stuff existed. I wanted to combine these two different roles together.“

She’s working on a new collection. She won’t say anything about it as it might still change, only that her approach to each object will remain the same: “When we were studying, it was always about making something noticeable, big. Now, I’m just thinking, what is the point? If you don’t want to wear it, what do you expect?“ she says. “At the end of the day, it is clothing. That was the reason why I didn’t go to fine art. I wanted something needed in this life, not just a beautiful piece in a museum. If I don’t want to wear it, something is not right, it is not there yet. It is important to look at it and be like, ’I want to have it.’ You know how sometimes you look at amazing pieces, and say, ’Oh, I wish I came up with it’? Now it has to be the same for me: ’Oh, I wish I had come up with this,’ but actually I did.“ —Ashley Simpson

All clothing and gloves by Talia Byre. Boots by Maryam Nassir Zadeh.

“There’s always a color in there that I hate,“ says Talia Lipkin-Connor, the designer behind Talia Byre. She’s speaking from her studio in East London, where she is draping and experimenting as she develops her forthcoming collection. The young creative—who grew up in the sartorial legacy and culture of her family’s famed Liverpool shop Lucinda Byre—is quickly becoming known for her cozy, elegant knits that both reflect her history and modernize it. “It always has to be a kind of mad color palette and something a bit off,“ she mulls. “I’ll be like, ’Oh, this is the most hideous thing I’ve ever seen.’ Then it will end up in the collection because you need that. Otherwise, everything is too nice.“

The 27-year-old designer, who completed CSM’s prestigious MA program in 2020, launched her semi-eponymous collection right upon graduation. As mentioned, the line is heavily inspired by the women in her family and the world her family created. “A particular kind of woman went [to Lucinda Byre], who you would aspire to be,” says Lipkin-Connor. “I’ve met a lot of people who said, ’Oh, it was too daring for me, but I would go and look.’“

Lipkin-Connor’s own garments, deep-hued (think a rich scarlet, a Barbie pink) and oversized with just off hemlines, carry this internal confident and self-possessed appeal. She studies pieces passed down from her grandmother and her friends as she designs, looking to the women around her. “I don’t know what happens, but somehow [the collection] ends up looking not too far away from the silhouettes I was inspired by originally,“ she muses. “I know when my mom came to the MA show, she was like, ’You do realize this is like Lucinda Byre, you have the same woman?’“

Today, the Byre woman may be a painter; she may be Lipkin-Connor’s younger sister or one of her friends; she may be you. “I’m very interested in that woman now: Who is she? Is she an artist? I get a lot of women who are artists, very intellectual women. That’s really important to me,“ says Lipkin-Connor. “It’s a woman who you would meet at a dinner party, who would be very clever and own the table. They might not necessarily be famous women, but I know a lot of women like that. I was brought up with women like that: 2.0, younger, slightly different world.“ The clothes are mainly produced close to home—by hand by Lipkin-Connor, in a very localized supply chain in Italy, and in collaboration with mills in the North that her great-grandfather’s tailor worked with. Lipkin-Connor also likes to work one on one with clients, much like her great-grandparents might have, or a couture artist who sees women seasonally. “One of the main things I’m conscious of is my history is so rooted in the original Byre, but I am very forward-thinking,“ says Lipkin-Connor. “It is not too nostalgic.“ —Ashley Simpson

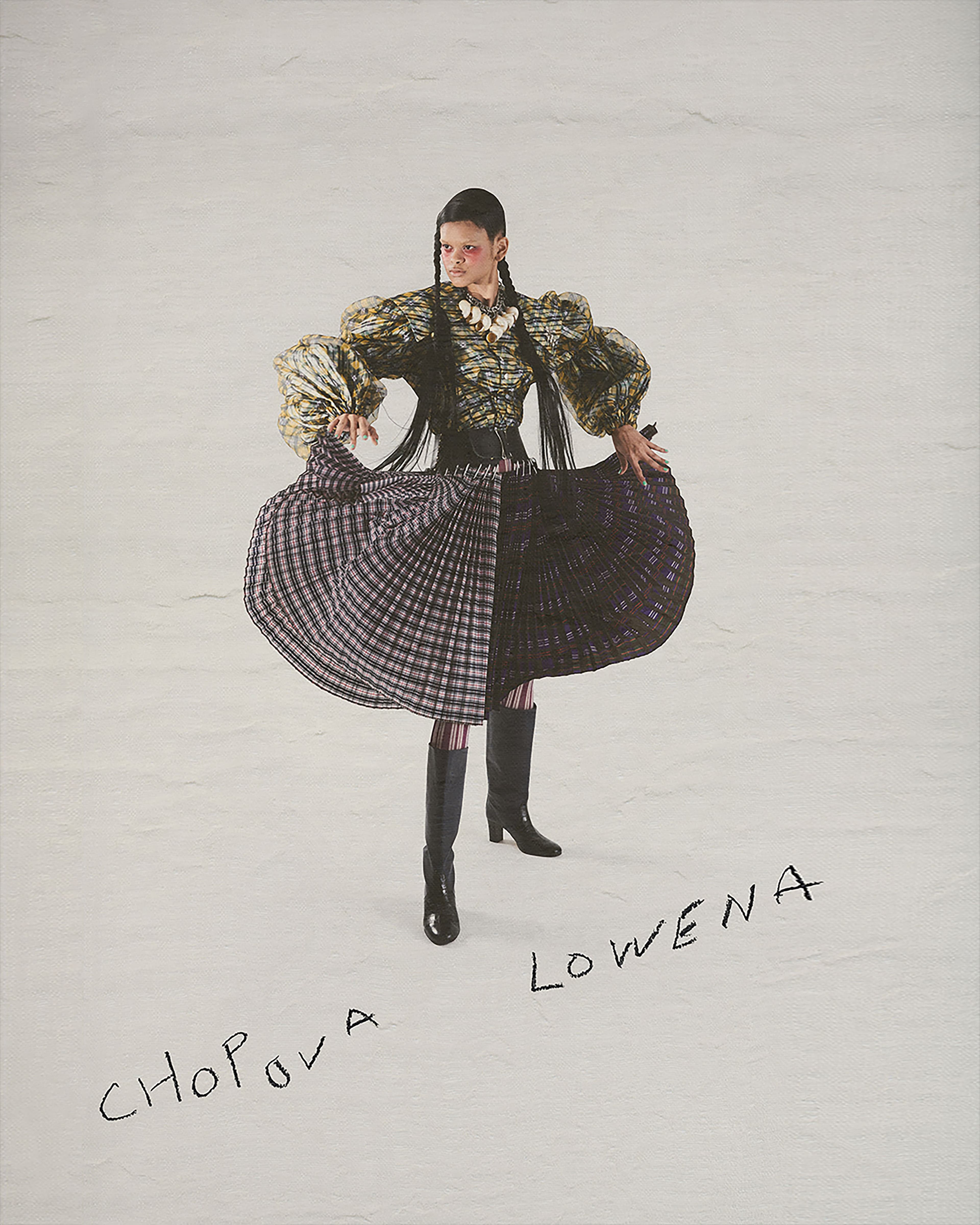

All clothing and necklace by Chopova Lowena. Boots by Maryam Nassir Zadeh.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.