Calida Rawles, The Lightness of Darkness, 2021

The Paintings of Calida Rawles Offer a Space for Healing and Self-Reflection

The works that Calida Rawles debuted at Lehmann Maupin in September—in her first New York solo exhibition and first presentation since Covid-19 swept through the art world—could perhaps be described as “pandemic paintings.“ The sizeable canvases, which face each other in conversational exactitude, submerge the viewer in the refracted aquamarine surface of the water in which her subjects float. Atemporal and semi-abstract, Rawles’s paintings don’t rely on depictions of death, isolation, and the mundane, as one might suspect from a body of work created almost exclusively during quarantine. On the contrary, they are sharp, placid, and contemplative, drawing us in and asking to be reflected upon.

Like many artists, Rawles was forced to grapple with the expediency of life and death in the wake of the pandemic. While her imagery and delivery are specific to her skilled photo-realist technique and personal interest in bodies of water, she was impacted by the same unprecedented thematic and æsthetic challenges faced by many artists. Although she admits her practice is primarily solitary and she was thus able to continue working, Rawles was aware of how the pandemic and last year’s climactic racial unrest affected the people closest to her. “Since I paint mostly by myself in a room, I’m always isolated for hours, so it probably wasn’t as hard for me as a transition because I’m alone a lot,“ she reveals, “but I understand how difficult it was for my family and my children. On top of that, what was going on politically and socially out in the world, I had a lot of mixed feelings with it. I was happy that [police brutality] was being acknowledged on a larger scale in our society since it is an issue that we’ve been talking about forever, [but] sad that it is happening, sad that it is continuing to happen.“

As a Black woman raising Black children in the United States, Rawles’s identity is inextricably tied up in her practice. She has never shied away from discussing racism, sexism, and the multitude of disparities and dangers that arise from simply existing in public spaces as a person living in a marginalized body or identity. Most Americans only gained awareness in the last year about some of the issues that have long plagued Black communities, such as medical racism, police violence, and income inequality, as lockdowns forced them to sit down and pay attention. “Since the inception of the United States, it has been difficult for us to find a resolution to issues of race,“ Rawles says. “It’s hard to get on the same page about how we all see identity. It seems so big, but on the scale of all of humanity, it’s only one thing.“ Marginalized and intersecting identities, generational trauma, collective memory, (popular) culture, and their interconnectedness are central to Rawles’s framework. “I would love to address race, identity, gender politics [in my work] because these are the topics that run around my head,“ she says.

Though the Los Angeles-based painter is certainly not alone in this sentiment, she foregrounds the personal in her work by making those most affected by these issues her subjects. They are her family, friends, and community, but they also include nameless (and more recently faceless) representations onto which viewers can and will project their own understandings and sensibilities. However, to see her subjects as solely political offers an equally tenuous perspective. Just as the pandemic forced many to reconsider the ways in which race, gender, and countless markers of identity influenced their empathic tendencies, Rawles’s suspended figures urge us to contemplate our automatic judgments and responses to the Black body. Through her use of water, she finds a personal balance between poetic symbolism and revealing truth. The challenging motif began to dominate her work after she started swimming for exercise. “When you come out of the water, you feel so much better,“ she says. “Maybe it’s the breathing aspect of it? It’s like a meditation in a way. By the end, I just felt so zen. I wondered if I could use water as a metaphor to discuss very difficult issues and they won’t seem so heavy.“

Rawles submerges her subjects in tenderness, allowing them to experience the same healing capacities swimming offers her. Inevitably, she confides, some of her subjects and viewers don’t have the same relationship to water, as the lack of access to public swimming pools and natural bodies of water and the sordid history of the Middle Passage have led to generational trauma that still haunts Black communities today. “I want to capture a range of different motions, not just strokes,“ Rawles says, “but many times my subjects will come and tell me they can swim, and they are not as comfortable [in the water] as I thought they would be. So there is a time where I am working to get them comfortable in the water before we can even begin.“ Still, the artist has always made an effort to depict her subjects as serene, never fearful or panicked.

Calida Rawles, ’On the Other Side of Everything,’ 2021

Some will recognize this imagery from the cover of Ta-Nehisi Coates’s début novel, The Water Dancer. The book, whose main character is an enslaved youth named Hyram, confronts the brutal history of the American South through the lens of magical realism. Hyram, who is saved from drowning by a mystical force of light, is rendered floating in the crystalline surface of the water, his head ambiguously submerged. As in Rawles’s most recent paintings, he could be in danger of drowning or just serenely adrift. The artist leaves that decision up to us, as the conversation evoked between painter, subject, and viewer is central to the dialogue she desires to cultivate—one that is essential to continue as many Americans move on and risk leaving the lessons learned over the last year and a half in the past.

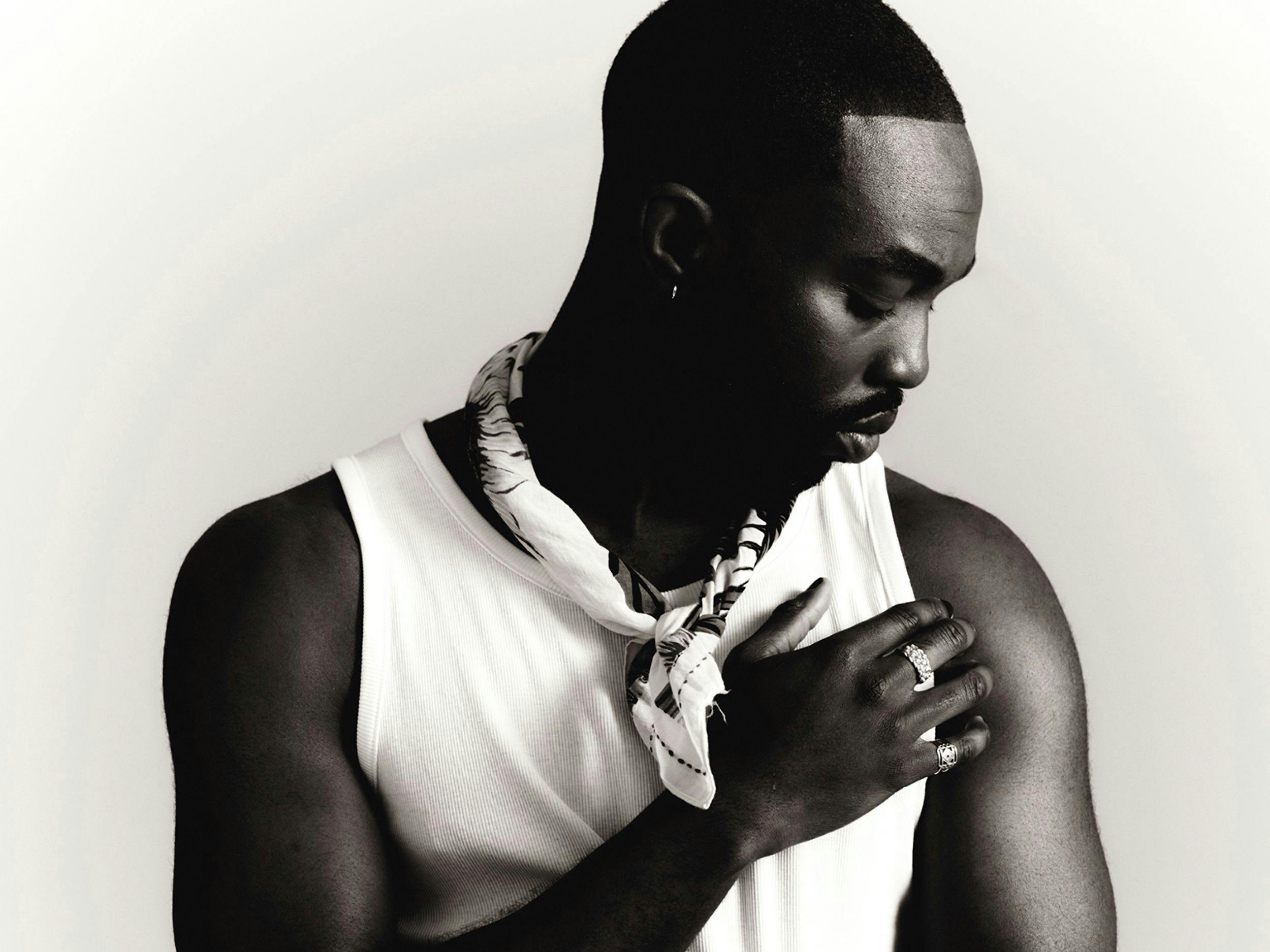

The five large-scale works presented in “On the Other Side of Everything“ at Lehmann Maupin are a departure from Rawles’s previous pieces, in which she painted her vision of femininity and fluidity inspired by her maturing daughter and the challenges she faces as a young Black woman. “Most of the figures aren’t in a swimming position. They almost look like they are dancing,“ the artist explains about her earlier paintings. “They just happen to be in water.“ But her new works are evidence of perhaps the most abstract manipulation of Rawles’s skillful, hyper-realist brush, magnified by a shift in subject. Over the last year, the Black masculine figure has become the focus of her work, perhaps subconsciously linked to the frequent circulation of video footage of police killings.

Meditating on Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man, Rawles contemplated an all-too-familiar question: “Are Black men invisible or are they hyper-visible?“ She found the answer in a quote from the novel, which haunted her throughout the making of this exhibition: “I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination—indeed, everything and anything except me.“ In Rawles’s new works, the pointed gaze shared by her earlier subjects has been abandoned for a heightened viscerality that reflects the viewers’ gaze back onto themselves, exposing the illusion of Ellison’s trick mirror. In place of an easy way to conceptualize and process grief, social isolation, civil unrest, insurrection, and racial reckoning, Rawles takes these “quick moments“ she captures in the worlds of her subjects and transforms them into echo chambers of self-reflection and metaphorical mirrors of our subjective realities.

Painting with reference photos taken underwater, Rawles positions herself on the other side of her subjects’ lines of sight. “I’m thinking more about the viewer than the subjects themselves,“ she explains. “We’re always on the other side of anyone’s experience and what they see. A lot of the subjects in my paintings now are looking out of the water at something I can’t see. I don’t know what they’re seeing, what they are experiencing. I can only see a small piece of them and a reflection that distorts the image that I can see. There is a limited view, and then we make a perception.“ For Black men, this view can become deadly. With these works, Rawles creates an opportunity to reflect on how our perceptions of those around us are always incomplete and structured through a distorted lens.

“On the Other Side of Everything“ is on view through Saturday at Lehmann Maupin, New York.

Calida Rawles, ’Dark Matter,’ 2021

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.