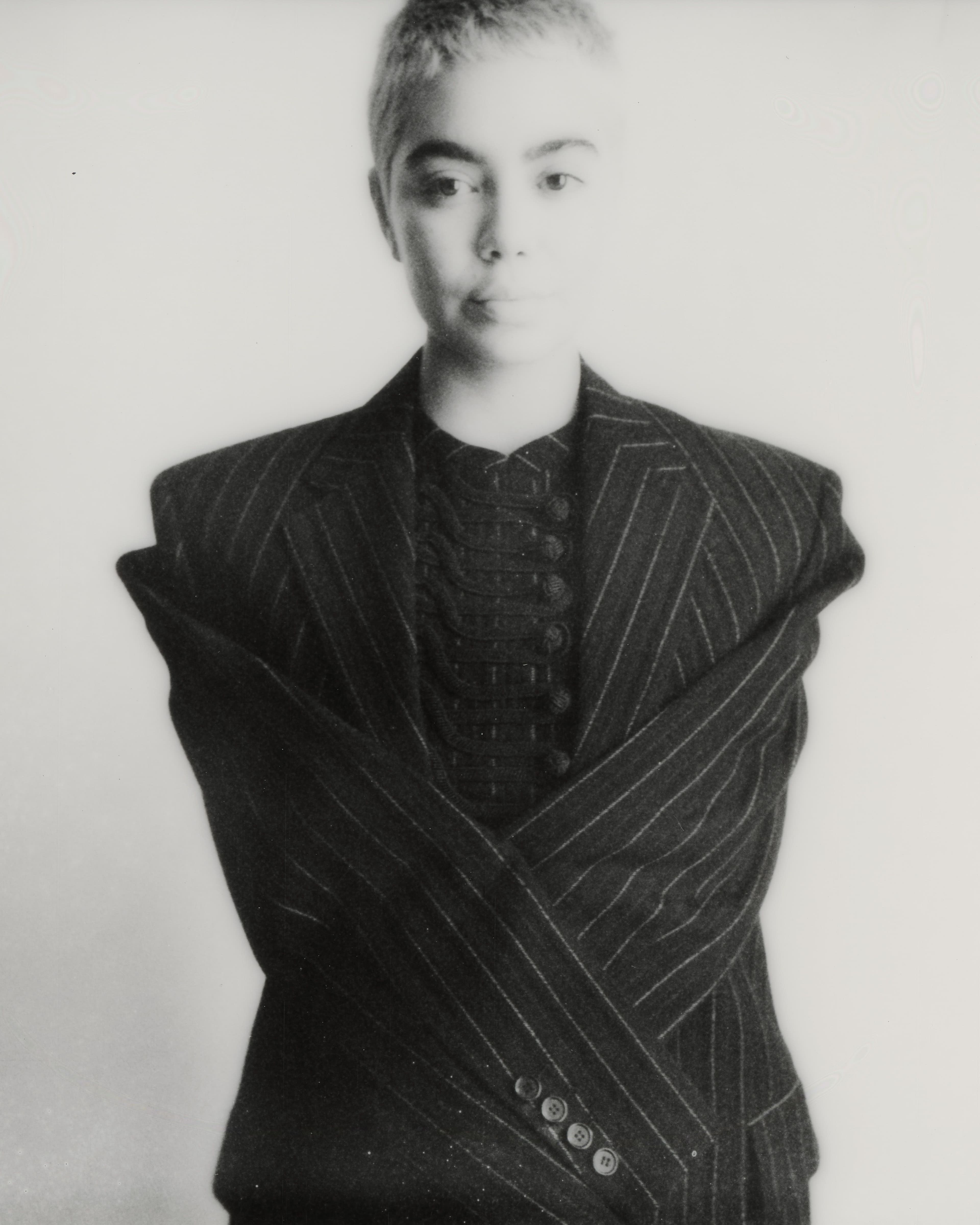

All clothing by Veronica De Piante

Auli’i Cravalho Says Icon Status Means Being True to Yourself

Auli’i Cravalho was recounting how she met her best friend in seventh grade AP World History when she started describing a teacher who hated her because she often defied him. He threw erasers at students and when he started offering extra credit for afterschool classes, she stood up to him and told him it was unfair to those with busy extracurricular schedules. “I have a problem with authority figures who push the envelope too far,” she said over Zoom.

Unsurprisingly, Cravalho has built her burgeoning career playing characters who don’t take well to other people defining the rules for them. At fourteen, she made her film debut as the voice of Moana, the barefoot Disney princess disrupting the status quo to save her island. Last year, in the Amazon Prime Video series The Power, she played Jos, who cyberbullies her over-ambitious mom, played by Toni Collette, for posting things online without her permission.

All clothing by Veronica De Piante. Vintage shoes by Celine, stylist’s own.

This year, she plays Janis Imi’ike, the artsy outsider who narrates the latest Mean Girls film, next to Jaquel Spivey’s Damian. Funny and sarcastic, with a precise hand for graphic eyeliner, here she rebels by ditching the rules altogether. Belting out her film-stealing eleven o’clock number, she declares, “I’d rather be me than you,“ and gives both a metaphorical and literal middle finger to the school’s popularity hierarchy.

Cravalho’s Janis also throws away dated jokes from the original (that her character is Lebanese, not lesbian) in favor of a Janis who’s comfortable in her queerness and doesn’t wrestle with her sexuality because she doesn’t need to. “Janis Imi’ike is a hot lesbian, call her a pyro-les if you want!” says Cravalho, who in real life is bisexual.

All clothing by Willy Chavarria

Like Cravalho, Janis is also Hawaiian—Tina Fey, who wrote the screenplay, asked Cravalho if she would like to change the character’s last name to better reflect her identity; Cravalho chose Imi’ike, which roughly translates to ’striving for the stars’ to reflect her character’s broader perspective on life. When Fey asked her, Cravalho was blown away. ’I was like, ’Oh my gosh, thank you so much that I can actually insert a piece of myself into this, a character that’ll live forever,’“ she says. “I love that I’m able to represent myself wholly in so many of my roles, and grateful that I can represent so many different communities as a young woman of color.“

Cravalho grew up in Kohala, Hawai’i, with her mom as a single parent buying groceries with food stamps. But she also spent time at her grandparents’ old plantation home, where they grew a lot of their own food—there were pigs, chickens, and avocado trees, as well as orange trees that gave her bad allergies in the spring. Relatives on her mother’s side were “constantly fishing,” she says. “Really, we lived off the land and the sea.”

All clothing and shoes by Hermès

She was a colicky baby; her mom sometimes says she developed her lungs from screaming for the first few years of her life. An only child, she would amuse herself by creating her own theatrical performances in her bedroom, enlisting imaginary friends or switching out different clothing items to play the different roles herself. As her energy grew, her mom tried to tire her out by enrolling her in activities like ballet and aikido. Cravalho also tried out for the USA swim team, which instilled in her an ability to take constructive criticism, a sense of competitiveness, and a hatred of the smell of chlorine. By seventh grade, her mom had enrolled her in boarding school at Kamehameha Schools on O’ahu, the largest campus of the highly regarded private school system for children of Hawaiian descent. “She saw more for me than I did,” says Cravalho.

Kamehameha Schools gave her a place to bond with her dorm sisters, join the paddle club, and hone in on her identity. When she was fourteen, she tried to audition for a local nonprofit event; the casting director, who was also casting for Moana, invited her to audition for the Disney film instead. Both she and her mom thought it was a scam at first, though ultimately, both were cast in the film (her mom voices another young villager).

Cravalho could easily have chosen another path though—by the time she graduated high school, she had five years of science under her belt and had studied honors in molecular and cell biology. In 2021, she was accepted to study environmental science at Columbia University. Ultimately, worried about her job security in the acting industry, she chose not to go. “I’m the breadwinner for my family, so I was like, ‘If I take even a semester in New York City and I’m not here in Los Angeles, will Hollywood forget about me?’” she says.

Dress by Bevza. Bodysuit by Haus Label. Earrings by Mozhdeh Matin.

Instead, Cravalho has embarked on her own mission to learn more about the world and how best to channel the platform acting has given her towards that. At The Power’s premiere, she showed up with a red handprint on her face, highlighting missing and murdered Indigenous women and law enforcement’s investigative negligence in these cases. In terms of the environment, she’s gone straight to the sources to learn about managing invasive algae and coral reefs, by working with loko i’a—ancestral Hawaiian fishponds, some of which date back hundreds or thousands of years in continual use. She’s also visited in situ coral nurseries in the open ocean with Kuleana Coral, a Native Hawaiian nonprofit dedicated to reef restoration, and has shared videos on Instagram raising awareness on how to care for coral reefs as part of her partnership with Kuleana and cat food brand Sheba. Last year, as part of her collaboration with social awareness nonprofit Pvblic Foundation, she went to the United Nations’s Manhattan headquarters to raise awareness about Small Island Developing States—the low-lying, coastal countries that have been the first to feel the effects of climate change as the ocean rises. “I really believe that young people can change the fate of climate change and the climate crisis,” she says.

“I know there are a lot of people doing great things,” she says, referring to some of her classmates from Kamehameha School. “What I hope is to continue my research and to continue learning but also to work specifically with Native Hawaiians and hopefully the larger government to change the public perception of just how important our oceans are and [highlight] what we can do to clean up like the harm that we’ve already caused.”

Dress by By Malene Birger

“[Environmental advocacy] does run in the family for me, if only because I was raised by strong women who raised strong women,” she adds. Her grandmother was part of her local Hawaiian Civic Club—a group of community organizations dedicated to Hawaiian culture—and lobbied for larger holes in fishing nets so that younger fish wouldn’t be caught. Every time her mother went camping at the beach, it was to go fishing—for food. But caring for the environment is also cultural and Cravalho wants people to remember that the land and the sea aren’t there for just tourism—they are ’āina, lifelines for Indigenous and Native people. She hopes to see more Indigenous and Native people leading environmental policy decisions.

In the meantime, she’s back to auditioning—when I ask her what she has in store for the new year, she laughs. “Girl, I’m unemployed!“

“I’m looking forward to getting another job. But I think my future is pretty bright, especially after this film,“ she continues. “I’ve worked really hard, and not that I’m going to rest on my laurels, but I think I can take a breath and not worry so much about what’s coming next.“

Dress by A——Company. Tights by Wolford. Shoes by Manolo Blahnik.

It’s only been recently—after reading the reviews for Mean Girls, something she usually doesn’t do—that she’s felt she could worry less about where her career was headed. Even stepping into the legacy of Lizzy Caplan and Barrett Weed for Mean Girls was daunting enough that she chose not to rewatch the film ahead of principal photography. She had nerved herself with the reminder that there must’ve been a reason she had been hired—the casting directors had obviously seen something in her.

Now, Mean Girls has taken both her memability and fame to a new level—a fan recently recognized her at a jimjilbang in Los Angeles, which was awkward, given she was naked. “Shout out to that girl,“ Cravalho laughs. “She was really nice though.“

Dress by Silk Laundry. Earrings by Agmes.

Recently, Cravalho buzzed her head and dyed it pink; she’s also been taking stunt and dance classes. She wants roles that challenge her and that don’t necessarily rely on beauty. She also won’t be playing Moana in the live-action remake, though she has mentioned before that she’d like to see more Indigenous people behind the camera and, indeed, will be an executive producer on the film. “I want to play more iconic women,“ she says. “I’ve been lucky in my career to play women who want to go beyond the reef or who look down the barrel of the camera and say, ’I’d rather be me than you,’ and flip everyone off. I just want to grow. I just want to have the space to cut my hair, dye my hair, and become a well-rounded individual. Admittedly, a lot of that probably needs to happen off the internet. But to me, being iconic is staying true to yourself.“

Mean Girls is now playing in theaters.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.