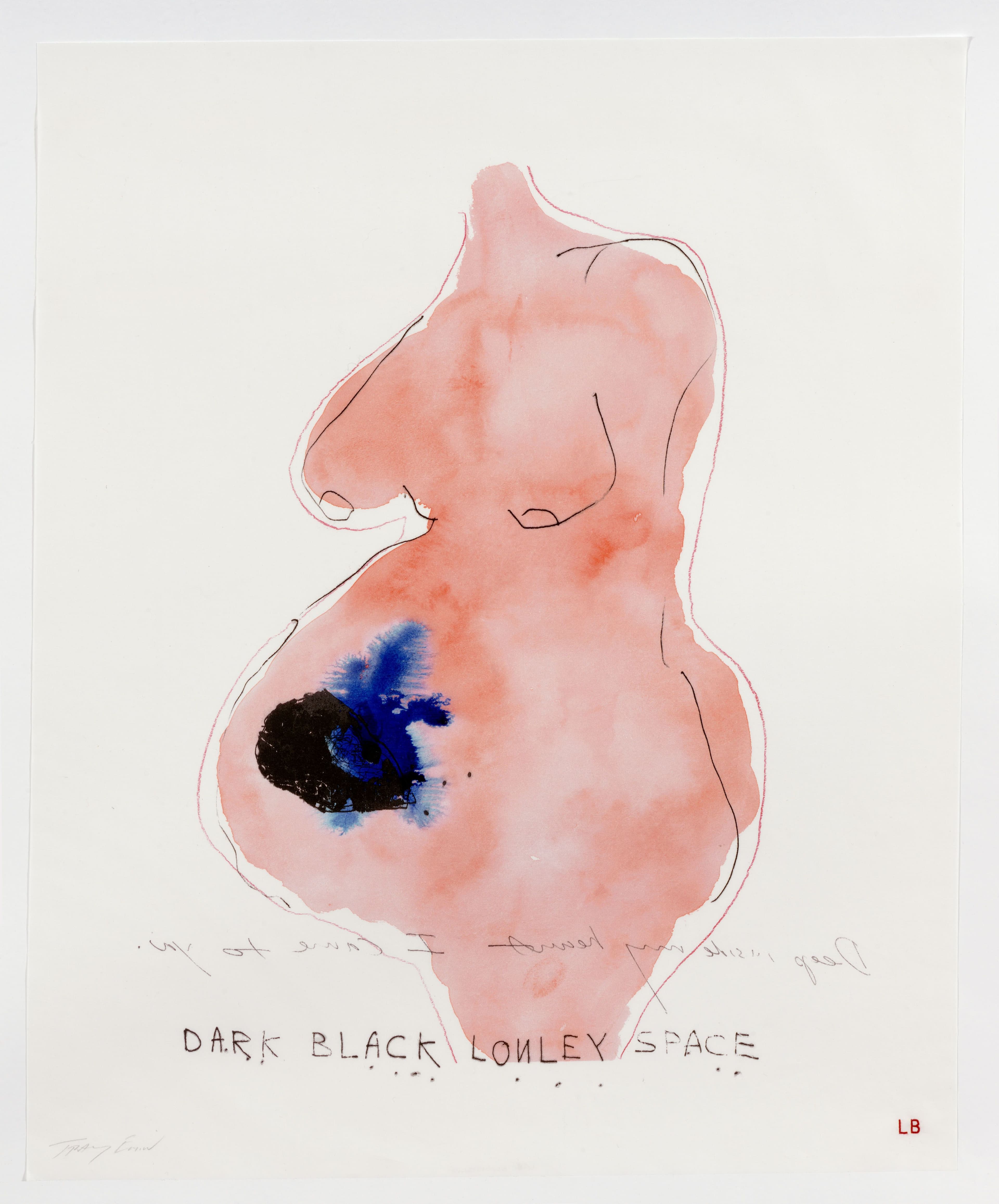

Louise Bourgeois and Tracey Emin, Deep Inside My Heart from Do Not Abandon Me, 2009-2010. Archival dyes printed on cloth, 76.2 × 61 cm. © The Easton Foundation / VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS, London / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

Fighting the Spread of Abortion Misinformation

The day after Lizelle Herrera was arrested on April 7, charged with murder for self-inducing an abortion, organizers with the Frontera Fund began to mobilize. That night, they reached out to other local reproductive justice organizations, began gathering supplies, and posted on social media to inform their local community in the Rio Grande Valley, where they serve as the only abortion fund, of the devastating news.

The next morning, at 9 AM, they arrived at the Starr County Jail, where Herrera, twenty-six, was being held on a five-hundred-thousand-dollar bail bond. Their goal was simple: “to make some noise, and just let Lizelle know that we were there for her and support for her. We’re standing with her,“ said Cathy Torres, the organizing manager of the Frontera Fund, at a press conference. “And we’re also letting the world know that this could happen to anybody.“ Within hours, the story sparked up national outrage. The following day, the county’s district attorney dropped the charges.

The arrest occurred against the backdrop of SB-8, Texas’s highly restrictive, vigilante abortion law, which prohibits abortion at the cardiac fetal activity stage—typically around six weeks, before most people even realize they are pregnant. The law, which went into effect in September 2021, deputizes private citizens, even outside of Texas, to bring civil lawsuits against anyone who performs or “aids and abets“ an abortion, effectively creating a bounty-hunting scheme that incentivizes lawsuits with an award of ten thousand dollars. The draconian law foreshadows where half of the country is headed in the coming months after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. Yesterday’s ruling paves the way for at least twenty-six states to pass abortion bans.

As the Frontera Fund prepares for Texas’s total ban on abortion, expected to go into effect thirty days after the overturn of Roe, its organizers anticipate a rise of criminalization and broad threats, especially against marginalized people. “Cases like Lizelle Herrera’s will become commonplace and seeking medical care will become unsafe,“ said Rockie Gonzalez, the group’s founder, in a press release. Although neither SB-8 nor Texas’s total ban includes criminal penalties for pregnant people, this can still be the consequence. Since Roe became law, seventeen hundred people have been arrested or legally penalized for abortion outcomes, according to the nonprofit National Advocates for Pregnant Women.

Abortion restrictions like SB-8 aren’t just designed to curtail access to one of the oldest medical procedures. They also function to sow misinformation, confusion, and fear—effectively narrowing access even beyond what is directly prohibited. “There’s the letter of the law. There’s the spirit of the law,“ says Magda Schaler-Haynes, a lawyer who focuses on constitutional and abortion law and teaches at Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health. “It’s certainly the case that [SB- 8] is trying to create a chilling effect on people who need abortion services, accomplished by fear and confusion and misinformation about the parameters of the law, such that people do not seek abortion care.“

It’s under this far-reaching, alarming influence that Herrera was charged with a crime that doesn’t exist. In fact, SB-8 explicitly states that it should not be “misconstrued“ to result in “the prosecution of a woman on whom an abortion is performed or induced.“ And under Texas’s penal code, any abortion resulting in the “death of an unborn child“ is not considered murder. Still, this did not protect Herrera from arrest. It took the Frontera Fund mobilizing and drawing attention to the wrongful arrest for charges to be dropped.

Even the name of the law, the Texas Heartbeat Act, is misleading; at just six weeks, the bean-sized embryo has yet to develop a heart. Beyond that, the law’s confusing, vague language is designed to stir uncertainty. Under the vigilante scheme, for instance, “aiding and abetting is not really defined in SB-8, except that paying for or reimbursing the cost of an abortion is considered to be aiding and abetting,“ says Melissa Shube, a litigation counsel with The Lawyering Project, which focuses on legal issues surrounding abortion. As a result, it is intentionally challenging to know how to support abortion access while complying with the law.

“Texas’s goal here was not to create a clear set of compliance parameters,“ says Schaler-Haynes. “The goal is to end access to abortion.“ By creating what she refers to as a “muddled field of information,“ the law could cut off some of the remaining avenues for accessing abortion.

These confusing restrictions could have been at play in the arrest of Herrera, who was reported to law enforcement by the hospital—despite there being no legal requirement to do so. “I want healthcare providers to understand that they are under no obligation to report to law enforcement if somebody presents as having had an abortion,“ says Farah Diaz-Tello, the senior counsel and legal director of If/When/How: Lawyering for Reproductive Justice, an organization working to reform the legal system. In fact, she says that doctors are able to provide patients with information on what symptoms to expect over the course of a self-managed abortion without violating prohibitions laid out in SB-8.

“The chaos and confusion [that SB-8] created was certainly intentional and intended to keep people from providing support to others who need an abortion,“ continues Diaz-Tello. As a general rule, “additional restrictions on abortion create additional confusion for people,“ she adds. To address this, If/When/How operates the Repro Legal Helpline, which walks callers through their legal rights on self-managed abortion, parental consent laws, and the parameters of abortion laws.

Since the helpline’s inception in 2018, it’s been operating with the understanding that Roe may be overturned. The conservative supermajority on the Supreme Court helped lay the groundwork for this reality, prompting states to pass or introduce an avalanche of abortion restrictions. This has drawn a predictable spike in calls. “We’ve already seen an intensification of the need for legal information through the helpline,“ says Diaz-Tello. “I think that we only expect that to escalate, especially in the immediate aftermath of the [Supreme Court’s] decision.“

As options for clinical abortion narrow, If/When/ How has observed and is working to counter the “continued, intentional disinformation about the safety of abortion pills,“ says Diaz-Tello. “Abortion opponents [are] trying to cast these medications, which are FDA-approved and proven safe in millions of cases in the United States and around the world, as somehow unproven, unsafe, or uniquely harmful.“

Following the Supreme Court’s leaked decision draft, the Frontera Fund was also quick to counter the developing wave of confusion. “Even just a leaked draft opinion really just muddies the water of people’s understanding of how the policy actually works,“ says Jessica Gomez of the Frontera Fund. “For most people, when they hear Roe v. Wade has been overturned, it’s ’abortions are now illegal.’“

“One of the things that we’re just trying to get out to our community is [that] abortion is still legal,“ adds Gomez. “It is not illegal. If you have an appointment, keep your appointment. If you need an appointment, make an appointment.“

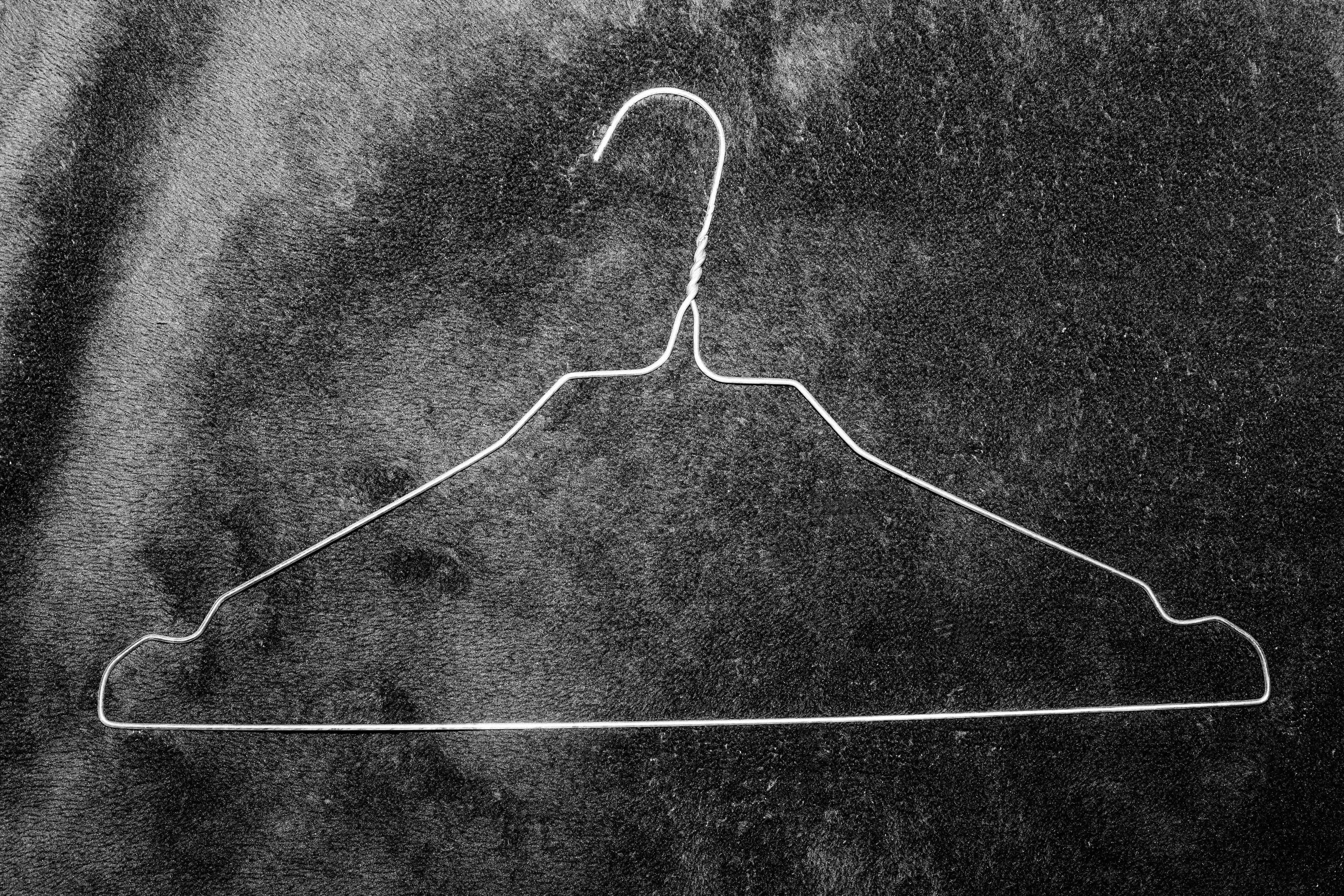

Laia Abril; ’Coat Hanger’ from ’A History Of Misogyny, Chapter One, On Abortion;’ 2017: “Desperate pregnant women have been known to probe themselves with knitting needles, whalebone, turkey feathers, umbrella rods and the infamous coat hanger. These can cause infection, haemorrhage, sterility and death. Abortion rights advocates worldwide have long used the coat hanger to symbolize what the anti-choice movement is trying to avoid. Ironically, the risky DIY method is seeing a resurgence in the United States, as access to safe and legal abortion falters.“

ABORTION FUNDS ARE KEY TO BUILDING TRUST AND SAFETY

As trusted and embedded community groups, local abortion funds like the Frontera Fund will continue to be crucial in helping people navigate safe pathways to abortion while confronted by financial barriers and misinformation and as states move to enact a deluge of punitive, disorienting abortion restrictions en route to the total bans expected in the coming months.

Texas’s patchwork of restrictions is a glimpse into where at least half of the U.S. appears to be quickly heading. The state’s other restrictive laws, like mandatory waiting periods for an abortion and a recent law narrowing the window for medical abortion, add to the confusing maze that pregnant people must navigate when seeking an abortion. “These laws are just designed to be this incremental, slow death by a thousand paper cuts,“ says Kelsea McLain, the health care access director of the Yellowhammer Fund, which supports abortion in Mississippi, Alabama, and the Deep South.

In anticipation of the Supreme Court’s decision, thirteen states passed “trigger laws,“ which will automatically ban abortion, with few exceptions, now that Roe has been overturned. Several laws took effect immediately, while most others have minimal waiting periods. Other states, like Idaho and South Carolina, have passed six-week abortion bans mirroring SB-8 which have been challenged by courts for unconstitutionality—an argument now moot with the end of Roe.

This is where local abortion funds—often equipped to fund the cost of procedures, travel expenses, hotels, and even childcare—can mean the difference between an abortion and forced pregnancy. SB-8 remains a case in point. Local funds in Texas have witnessed a drastic increase in the need for transportation to clinics in other states since the law went into effect. For instance, Jaylynn Farr Munson of Fund Texas Choice says they have gone from receiving fifty to three hundred calls per month seeking this support. But they only have the funds to support a third of callers. Similarly, abortion funds in neighboring states, like the Yellowhammer Fund, have witnessed a spike in calls from Texas.

It’s common for people to travel out of state for an abortion, with just enough money for gas but not a hotel. “We’ve had people drive all night long from South Texas to get to Oklahoma,“ says Susan Braselton, who coordinates volunteer clinic escorts at Tulsa Women’s Clinic for the Roe Fund. “[People] will be there sleeping in their car when we get there to open the clinic in the morning, and then as soon as they’re finished with their appointments, they turn around and drive back. It’s really sad.“

Beleaguered Texans, however, are no longer able to show up at the Tulsa Women’s Clinic because a copycat law modeled on SB-8 went into effect in May. It is likely to be followed by a total abortion ban in Oklahoma this summer. Soon, the clinic may need to shut down. “We’re all scrambling,“ says Braselton. “We’re trying to get some information from [abortion funds in] Texas about how we might offer transportation costs.“

Along with these physical barriers, the anticipated abortion restrictions will add to the confusion and fear already pervasive in states like Texas as part of the broader misinformation apparatus of the anti-abortion movement. “Misinformation is the biggest deterrent of all of this,“ says Farr Munson. “Because even if something is not illegal yet, just hearing about it in the news is enough to deter people or make people think it is.“ Abortion funds like the Frontera Fund, Fund Texas Choice, Yellowhammer Fund, and the Roe Fund are all vital in not only supporting local abortions but also restoring trust and safety within communities.

To stem the rising tide of misinformation, the Frontera Fund worked on developing a mass campaign to educate people—from doctors to pregnant people to local officials—on their rights and responsibilities under the state’s abortion laws. “When you talk about educating people, we really have to boil down to a community level and really center the needs of the community,“ said the Frontera Fund’s executive director Zaena Zamora at a press conference. “That’s something that we really, really want to work on.“

To a degree, countering misinformation is already baked into the work of local abortion funds as they help people navigate their options. For instance, Farr Munson was unaware that it remained legal to seek an out-of-state abortion under SB-8 until connecting with Fund Texas Choice, which financed her hotel stay and travel to Maryland for an abortion. Now that she works for the fund, she has realized that her confusion is widely shared by many of their clients with the same questions.

Often, it can be something as simple as a reliable voice on the other end of the phone that can cut through the confusion and fear. Farr Munson recalls the relief she felt when she first called Fund Texas Choice for help with her own abortion. “It might be like one of the best moments of my entire life,“ she says. “I felt like I was seen and heard and so validated in a way a lot of us don’t even feel like in our regular lives.“

Read this story and many more in print by ordering CERO04 here.

Laia Abril; ’Hippocratic Betrayal’ from ’A History Of Misogyny, Chapter One, On Abortion;’ 2017: “In February 2015, a 19-year-old woman took abortion pills in São Bernardo do Campo, Brazil, then went to the hospital with abdominal pain. After treatment, her doctor called the police, who handcuffed her to the bed and forced her to confess. In Brazil, abortion is illegal under most circumstances and doctors are known to break their confidentiality code in order to denounce women who try it. Patients accused of attempting abortion have been detained in hospitals for weeks and even months.“

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.